Robots of Paris

Andrea Kriz

He stops by that café down on the corner and gets one plus a coffee, black, on his way to the office and leaves it half-eaten on his desk by ten in the morning. All his friends in Germany tell him it’s not supposed to be like that, rave on about flaky layers and beautifully browned crusts and so on, so it must be some baker, or maybe that waiter with the ascot who always glares at him when he walks in, getting his petty revenge. No, it’s not easy being an SS officer in this crummy city.

At this hour of the morning, Riess’s usually waking up at his desk with keyboard keys imprinted on his face, trying to remember which robot-fighting gang member’s e-arrest form he’s been filling out, or whose Labor Corps exemption he’s dealing with—like he doesn’t realize they’re all faking it, bastards—or explaining why he electrocuted that AMP dealer last month. Unless he’s rolling out of bed at five in the morning, getting a couple sets of push-ups in and briskly walking to work, then it’s stopping by the café, doughy croissant, etc.

So he should be glad to get out of the office. But he’s not. He’s downright uncomfortable in the wake of flashing red-blue patrol skycars, peering into this alley. Standing in the cold dawn makes him realize how much he appreciates the morning routine, waiting in line in the so-called authentic café, all those French teens talking smack about him, sticky floors, news and cigarette kiosk shutters slamming outside. It’s dead quiet.

“We’ve got reports of a monster running around,” Aude Schiller told him back at the office, with a sarcastic smile. “A metal beastie.”

“Can you say hallucination?” Riess jibed.

“AMP, drug of choice in the slums, doesn’t make you hallucinate,” Aude said. “It just gets you high. Gives you energy, like you can do anything in the world.”

“Well, I wouldn’t know,” Riess mutters to himself now. “I’ve never tried it.”

Although some of his panzer friends used to pop it like candy back when it was a proper drug, restricted to the military. It reminds him of the time he served. Quietness, dark holdouts in crumbling cities, flashes of gunfire here and there.

There’s none of that now. He’s peering into the alley instead, gloved hand splayed against the faintly damp wall because there’s no way he can take it any longer just standing here, waiting for whatever miliciens drew the short straw to come back with reconnaissance or coffee or fresh baked pastries or what. The last reaches of red-blue light flicker on the puddle behind him as he ducks under the tape, LEDs alternating between POLIZEIABSPERRUNG and POLICE ZONE INTERDITE.

A cop detaches himself from one of the skycar radios and comes jogging over. They’ve set one of the newbies here to babysit him. A young guy, mid-twenties, and the breath puffs white out of his mouth as he hesitates, shifting from foot to foot.

“I’m going to scout a bit outside the perimeter,” Riess informs him. He’s clearly wondering whether to phone up Aude or text her for approval. Riess twinges with irritation.

“Have you got your gun sir?” the cop finally asks.

“Of course,” Riess snaps, and wants to add, “I’ve had my gun, son, since before you were born.” First time he offed someone had to be when he was eighteen. When he was twenty, he was crushing riots in the frozen wastelands, hijacking mech suits—those ancient ones without personality circuits, that you could just jump into—and taking them for joyrides. So he can handle whatever the situation is here now.

The builder’s some French teen. He runs over the info Aude gave him back at the office as he blinks five times in rapid succession, obligatory echo of that electronic woman from the instruction vids, activating his night-vision contacts. Leader of one of those robot fighting gangs. The Flying Hares. Marcel Volant—we’ve dealt with him before. Have they? Any French name to Riess isn’t worth remembering. They’ll ship the kid off to the Labor Corps most likely, they’ve got that whole process electronic now, takes like twelve clicks and they’ll just inject the microchip into his arm, have it wrapped up by noon.

Of course it might get complicated depending on how exactly it’s done, might have to drum up a firing squad, do the whole shebang. Maybe they can use the schoolyard again. That way they can take advantage of the zoning restrictions to keep the protestors out, even though the city officials have gotten wise to them, are pushing back against it now… he’ll have to check where the litigation stands.

Back in the day they would’ve shot the lot of ‘em. The murderer for murdering, the protestors for protesting, the officials for officiating, that ascotted waiter for being an ass and giving him half-baked croissants. They used to be nice to you back then—they didn’t have a choice. Now this building of robots that can slice up people, Christ. Like that poor corpse back there, under the tarp in five pieces. But he wasn’t military, so maybe they won’t have to go through the hassle of the firing squad, freezing their asses off in their stuffy uniforms, and in the end Riess probably having to go up and shoot this Marcel kid in the neck anyway because these guys couldn’t hit the side of a barn if it was tied down, shitheads.

Berlin’s oddly specific about these types of things. If the kid did it with a meat cleaver he’ll get thirteen years of hard labor, but if he did it with a robot he’ll definitely get the firing squad.

Then Riess spots him. He slips back around the corner expecting the kid to have heard the crunch of his steps through the snow and dart away… but he doesn’t. He’s tracing the bricks in the wall in front of him with bare fingers, hatless and in a light jacket. Riess shudders through his layers of coat and ushanka seeing him like that.

Enhanced reality text appears in Riess’s peripheral vision: 95% Confidence, Marcel Volant, Age 18, Eye Color Brown, Height 176 cm, Last Seen Wearing, floods of info he’s constantly telling the engineers he doesn’t fucking need—he’s looking at the kid, right? He continues tracing as Riess murmurs instructions to the waiting cops into his earpiece, steps up to the kid, gun drawn.

Like he’s waiting, the thought flashes through Riess’s mind. That dark feeling in the pit of his stomach rises.

“Hands up!” he barks.

Nothing. No sound of running, no back-up coming in the form of flashing skycars skimming toward them. Did those idiots not hear him?

Riess will say it into the earpiece again, louder, but first he wants this kid, Marcel, to face him. See his eyes widen and his muscles twitch, maybe even fall over in a comedic attempt to flee, get some confirmation out of him of Riess’s presence here.

Instead he gets a high-pitched giggle.

“C’est vous,” Marcel says, and a trembly grin spreads across his face. “C’est vous!”

Should he have brought his translator along? Riess wonders. His milicien, Frédéric, is hanging by the skycars and trying to bum off a cigarette, if he knows him at all. Although even Riess understands what the kid just said. It’s you.

And Riess knows Marcel knows damn well what he said, they teach them that in school. Probably first words they learn, because that’s the only German most of them will ever hear. Hands. Up. Under. Arrest. And if that wasn’t enough, there’s this uniform, this gun. Riess walks up and jabs the barrel right into his chest.

“I said put your hands up,” Riess growls.

Still that stupid grin. Maybe he really will shoot this kid, point blank. That sound will bring all of the idiot cops running. He’ll figure out the paperwork later, say the kid resisted or something. It’s almost less than what they have to do with the firing squad, guilting people into doing it and then documenting everything from the maintenance on the rifles they used to what they fed him the day before for the Ethical Executions Committee, and hounding the Town Hall for the death certificate after the fact…

But wait. The kid looks familiar, Riess thinks.

Curly dark hair, freckles.

For sure they’ve met before.

No, he’s too young.

Marcel takes a step back, so the gun’s no longer touching his chest. Riess’s grip tightens, his finger clenches around the trigger.

Marcel takes another step back.

And then he turns and walks off and leaves Riess standing there, trembling the handgun at thin air.

“Where the fuck were you?” Riess blurts.

“We saw him the same time you did, sir,” the cop says through a mechanized voice filter. “Dr. Schiller said you could handle it.”

That bitch. Always putting him on the spot. Insinuating he’s too old and out of it to keep up with this investigation in the field, then, when he’s out here, telling all the kids to hang back and watch a crackshot SS officer go it alone.

As if they didn’t have enough trouble maintaining a presence in the police force without all these games she’s playing from within. Aude Schiller, with steel-blonde hair, her blouse buttoned tight across her chest, carefully up to her neck, especially when she sees him now. Riess knew her back when she was still working on that psychology degree, and now she’s a police detective with that Doctor still tacked on her name.

Got her eyes on his job, he knows.

“We’ll fly around and catch up to him, sir,” the cop, or maybe another one, beeps.

“I’m going after him,” Riess says.

“That’s unwise. We have the milice canvasing the ground—”

But he’s off, sprinting in the direction where the after image of Marcel is still seared in his mind. Out of the alley, huffing past tenement buildings so cookie-cutter he feels like he’s treadmilling past the same sooty wall over and over again.

Rue 16, his eye-text tells him as he passes, Rue 18… Rue 23…

Makes him feel bad for the kids who have to live in these banlieues. Kids should have plenty of space to run around in, like he did when he was little. Through the forests, airplaning through the halls of their English manor house. She’s right, Aude. He’s grown weak, doughy. Even ten years ago this would’ve been no problem for him. The running definitely, even the shooting. He would’ve done it with all those bastards watching.

When he first arrived in Paris, they had to tell him this wasn’t like any of the places he’d been before. Russia, where the natives would smash you in the head with a bottle and leave you in a snowbank. New York City, where they’d blow you up with a flip-phone and a bunch of crap they found in an alleyway. Nobody will try to kill you here, they said soothingly. They’ll just sort of sulk. Give you half-baked baked goods.

Even so, that’s not enough for him. Riess doesn’t just demand compliance, he demands respect. No, not even that, he demands just that certain look in their eyes… that they stop thinking when they see him, that their brains switch to bare-bones survival.

At least he used to.

He’s blinded by oil lamps swinging from tin sheet eaves, stumbles on a dealer packing up the last of her illegal batteries and pills. They end like a razor’s edge, the tenements, and suddenly it’s just seas of shanty sprawl from here on out, sloping gently up and down, spazzing out the map module of his contacts, which he keeps telling the engineers needs to be separate from the night vision exactly for this reason, he can barely see through this wall of nonsense—??? Street, a5b// (&^ Avenue—so he just shakes his head three times, shuts it off.

Fire-hazard central, here. In the office they get fined for putting chairs out in the hallway. The inspectors would blow a gasket if they could see this, nests of wires tangled around poles, mechanics welding hunks of metal right up against wooden shanty walls.

Slush splashes around Riess’s boots as he steps down from the curb. Toward an AMP junkie who blinks up at him with red-irised eyes, like it’s just a costume that Riess is wearing, before back-pedaling away.

“Shit! SS!”

“Did you see—”

But the junkie’s already yelling and pointing, and people erupt out of every crevice to gawp at Riess. If you could call them that. Cockroaches would be better. Riess plows through them, in the vague direction that they’re stealing looks in, a narrow alley that can barely fit his frame. He’s heard on the radio that the Urban Planning Committee wants to bulldoze all this down, build new tenements up to the river because it’s more financially viable than letting them build their shanties, burn them down, build up again over the ashes, rearrange themselves like those microbots he heard about an inventor premiering at the World Fair.

He wonders if you dug down you’d dig up layer upon layer of shanty town, like those ruins of Ancient Rome, Pompeii. Maybe if you plastered in the voids in the ash, you’d recover casts of insurgents at the very bottom layer, stranded American parachutists staring up at death raining down at them, circa 1950 or so. He wishes they hadn’t blown it up in the first place. Then he’d be walking through beautiful architecture, houses like tiered cakes, like they have in the city proper, instead of this stinking gutter. Of course they’re raising that horrible Vault over it now, step one of the multi-tiered city plan, so soon it’ll all be one and the same down here.

There.

Suddenly Riess sees Marcel. He’s waiting. Lounging next to a robot fighting ring, in a square of sorts, but as soon Riess pauses to catch his breath the kid turns and strolls away.

“I’ve got eyes on the perp—” Riess says into his earpiece.

But police skycars bellow overhead, drowning him out, and the crowd’s stampeding like a herd of buffalo in those cowboy books Riess used to read as a kid. The ‘cars fly off in a cross, four cardinal directions, everywhere except where they fucking need to go. Suits him just fine, Riess thinks, as he half-pushes, half lets himself be pushed after his last glimpse of Marcel—the kid’s black leather jacket.

Past the fighting ring walled with sandbags, a machine with scythes for arms crumpled in a heap in its center. Its builder ducked down in crash position beside it, wrench still in hand. Riess doesn’t like flying in the skycars—gives him motion sickness—and he doesn’t like those things either, the robots of Paris.

Five or six years ago, the kids in the slums started building them, in the shape of humans, animals, monsters that’ve never existed before, like that junk’s gained life of its own, resurrected. His friends at the military dump tell him they don’t even fire warning shots at the scrap thieves anymore, they have to shoot to kill otherwise the scavengers don’t give a damn. You can see the heaps of junk metal dancing up blue, misty in the distance now that the tenements are out of the way. The sun’s rising in that direction. And the alley Riess wheezes up slopes toward the dumps too until it swerves around a smoking ruin—or maybe that’s just the freshly fallen snow melting on top of it—and slowly climbs up again.

“You get him?” Aude Schiller’s voice says in his ear as the racket from the square fades behind him. “Do you want backup?”

“No,” Riess growls.

“You can just shock him, you know,” Aude says. “You’re not a ghetto cop in one of those war flicks.”

Riess doesn’t bother answering.

“Don’t tell me your gun doesn’t have that feature?”

He didn’t need it, he told himself, when he left his slim smart pistol in the drawer, picked up the twice as heavy Walther he’d carried with him for the past dozen years instead. He doesn’t know how to work it, the new tech. He can’t stand these new, pathetic excuses for weapons—not having the option to just kill them all.

The nerve of these kids these days.

In Berlin they want to come over, study abroad—somewhere safe of course, like Paris, not New York, not Stalingrad—and protest. Because it’s just not right having native culture wiped out like that. Their parents let them grow up soft. At that age, Riess partied with the Skullheads back in Russia, back when they had carte blanche to kill everyone in every village they came across, stacked them up dozens high…

…and then those college kids stage something they call a ‘Die In’, lay down on the steps of the courthouse, in front of Metro stations during rush hour, even splatter red paint on themselves like the alleged victims of the police and SS.

They don’t know how similar they looked, lying in the snow. How similar they are.

He crests the top of the slope—and Marcel’s at the bottom of a staired lane, waiting.

Water’s sloshing somewhere behind these shanties—offshoots of the river, canals? But no, those would be frozen so it must be the real thing, the Seine. He can believe that it’s breaking free of the ice, like his breaths are panting free of his body after all that running, like his body wants to break free of all these layers of coats that are only suffocating him now.

Time seems to have accelerated. Years slough off his shoulders like the snow sliding off a holey roof beside him, fwoomph. It hasn’t been plowed here, of course, and the steps are slippery with half-eaten ice. He takes them one by one, expecting Marcel to turn tail and keep running, but he doesn’t. The kid just stands there, reaching up to a line of dripping icicles above him. It does have an interesting effect, the way the sun gleams through them while the last traces of night disappear.

Part of Riess is disappointed. No one’s around, the skycars are gone, even the buzz in his earpiece has faded away. It’ll take the others minutes at least to come running. He’ll have to shoot him. Like an animal he’s chased down for just this moment, to see him turn.

Adrenaline pumps through Riess’s veins as he aims his gun. His heart, his brain, expects it. Even the houses are expecting it.

But Marcel turns toward him in the sunlight-moonlight and he’s smiling.

“Do you remember me?”

It hits him. He has seen this kid before. His father, rather. Professor Volant.

Those guys in Intelligence that Riess wanted to be friends with, get his foot in the door with, they got real interested in the Prof’s research. So Riess made contact, made up some yarn about how Volant was 1/128th Jewish or something, and took him in—but then they turned around and handed Volant right over to the interrogators, who Riess was not friends with, even though they were all SS, higher ranked than he was, all lumped together by association.

Because that’s all they’re good for, right? The dirty work. It doesn’t bother them, it doesn’t harm them like it would harm the others, the oh-so delicately honorable Wehrmacht, those shits in Berlin, signing the orders and then standing in front of the camera with their long faces and lines of medals talking about ‘regrettable circumstances’ after the fact…

Yeah, those guys in Intelligence lost interest in Riess ASAP. Left him to languish, as an Assistant Director of Criminal Activity—no, Criminal Investigation—that doesn’t sound any better—Department of Criminal Investigation—right up until someone like Aude Schiller comes along and forces him to retire or he dies of old age. Whatever comes first. Whatever.

“What’re you laughing at, you little shit?” Riess snarls, mostly because he remembers Volant’s brat sniveling against the window as they took his father away, probably thought they were going to shoot him, and now he wants to see it mirrored in the teen boy’s eyes. “I could kill you right now, you know, I could shoot you in the fucking face and let you bleed out in the dirt—”

And then the wall bursts beside him, and Riess is flat on the icy ground, gun skidding out of his hand as a metal claw clamps down on it. It keeps pressing, until his hand pops under the pressure. He hears the bones crack, feels pain whiplash all the way up his arm, even though the claws are intertwined with his own fingers like a lover’s.

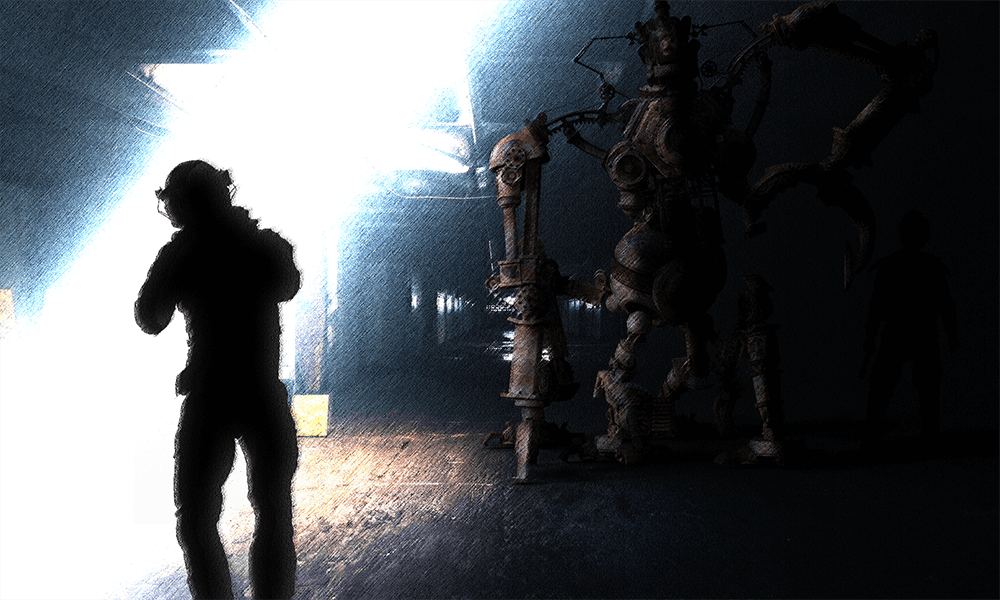

He must’ve screamed, because someone—Aude—is shouting in his ear, “Udo! Udo! Where are you? We can’t get reception—” but another mechanical arm delicately plucks his earpiece out, tosses it after the gun. He hears it skidding across the pavement as he rocks up to his knees and stares at the robot.

The jagged hole frames it like a halo in one of those paintings of saints, dripping plaster and water. It’s got so many legs. The big ones pin him down again, against the dirty snow, the thin mass of little ones whip toward him and he can’t move. That dark feeling surges up his stomach, fills up his throat until he thinks he’s going to puke.

Is it going to dig into his organs?

Is it going to rip his heart out? It’s beating so fast it might come out all by itself.

“Do you remember me, Herr Officer?” Marcel giggles, but Riess can’t tear his eyes away from the robot. “Do you remember… this?”

Is this thing it, Riess wonders? The robot his ‘buddies’ had Professor Volant build? Back when they were all in the same building, before the torturers got enough funding to move out, to expand, you’d run into them by the water cooler, in the gaps between filling out paperwork, leading their battered, bruised prisoners around. The confession extracter, they called it.

They tested it on the Professor extensively, before they shipped him off to one of those labor camps, factories where they make T-shirts, flatphones, Volant in such a state Riess doubted that he’d survive a day.

Riess still remembers the screams, cradling his head in the break room, thinking this isn’t what I wanted, all this fucked up shit.

I just wanted a bit of power…

I just wanted a bit of fun…

It’s different now. The robot. It’s got this ridiculous mask stuck on it. A plague doctor’s, beaked like a vulture. Where did the kid even get it? Riess’s eyes blur. Above the ‘bot, in the sky, he sees the doughy crescent moon.

“You feel that?” Marcel says, crouching down next to him. “What you’re feeling now?” He’s switched totally to German. “That’s fear.”

Is that what this is? Riess wonders. He’s fading already. Not the man he used to be, or maybe even ever thought he was. For decades now he’s been consumed by the hesitation he felt earlier tonight, unable to pull the trigger. Half-baked. Unable to savor this sensation.

Fear. Funny. He always thought it would feel—more deserving than this.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of “Robots of Paris” on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)