In The Weave

David Whitmarsh

In another thread, Mother’s ridges flashed at me, but I could not let go of my fading self.

The wind died. Stillness such as I had never known. The clouds above were high, thin and high and scarcely moving. A gap appeared. Beyond was black sprinkled with pinpoints of light that stayed still as the broken cloud drifted across the sky.

In this cold, thin strand, my mother lay dead beside me. I felt the life seeping too from my own body, my sight dimming.

Offspring of mine! My mother’s facial ridges rippled brightly, flickering with her irritation.

The wind whipped around the nest’s lee as it always did. The bright clouds above scurried their eternal race across the sky. The nest was warm. The grub that Mother laid before me was warm.

That thread was far from the first in which my life ended, but the manner of the ending disturbed me. It was lost not just to me, but to Mother and Grandmother too, and it seemed to everyone in our village. My thoughts dwelled also on that strange sky, the myriad little lights that shone high above.

What lies beyond the clouds? I asked Mother as I sank my mandibles into the squirming flesh, and sucked.

Her answer was terse. The clouds are the limit of the worlds. There is nothing above.

Grandmother blinked one pair of eyes, then another. There were stories. The glow on her speech ridges was feeble, but readable. A Visitor from above the clouds, in distant folds of the weave, distant even when I was seeded.

It was seldom that Grandmother could rouse herself to speak. Her mind was failing as her weave wore thin with age. So few threads remained to her.

Her crusted eyes closed again.

Rip-storms bring destruction and thereby renew the forest. The biggest, oldest trees can be as tall as an adult is long, and they spread their branches wide and shade the soil beneath from the cloud-light so nothing new can grow beneath. When they are so big they can no longer furl their branches to let the storm slip over them, a rip-storm clears them away, allowing new life to flourish. It is a part of the cycle, of the natural order of things.

This storm cleared not just the old growth, but everything. Everything living, and much that was not. The soil itself was being scoured away. Even as I wondered whether I could hold on until it passed I felt the pain of my carapace cracking from some unseen impact.

I walked through the village behind my mother. Her anterior eyes blinked as my segments rippled to a stop. She turned so that I could see the words on her face. What troubles you, offspring of mine?

Upwind, the branches of the trees waved and rippled, shielding the fields in their lee.

I have died again. I know one small death is nothing, but I feel so many. I said. Was it always so?

What is always? Her words were erratic, flickering and shimmering. Who can tell amongst all the pasts we can see and all those we cannot. Who can trace all the warps of the weave? The pasts are unknowable as the futures.

She turned and I followed her tail, wondering at her impatience, wondering also at my own dark mood. We are seeded, the threads of the weave are spun, and in each we die. Sometimes sooner, sometimes later. I knew there would come a time when my deaths would come faster than the spinning of new threads and I would diminish, as Grandmother did, but I was young. Daily I felt the weave thicken and new patterns emerge. I felt brighter, sharper.

Despite these endings, these threads torn from me, I still grew.

There were no clouds.

I pulled away my focus, returning to a thread where I lay quiet and warm in the nest between Mother and Grandmother. All but one lateral eye was closed, and that watched my mother, who was speaking, but not to me.

Was it always so? she said.

I cracked open an eye on the other side, where Grandmother lay.

Grandmother’s face glowed with the feeble light of her own words. Always so. So many little endings where the boldness of youth leads to misadventure. This is how they learn.

But these are not little deaths. Mother’s ridges flashed. Everyone dies. The village, the world. Everyone. And this not just in fine fibres, but great cords of the weave.

There are stories…

Shine me no stories, said Mother. What matter the infinite unknowable pasts. We live in the multitude of present moments. Wisdom is in the weave.

I recall no such endings in my pasts. Flickering mumbles chased around Grandmother’s face.

At the edge of my vision I saw something bright flash across the clouds, a spark angling across the sky in the time it takes to blink twice.

Stones sometimes fall from above the clouds, Grandmother said in a soft light.

Had I not seen that light in the sky, I might have thought her words to be merely ramblings from lost threads. Tell me a story, I flashed to her, but her face glimmered only with the incoherent scintillation of one who has lost focus.

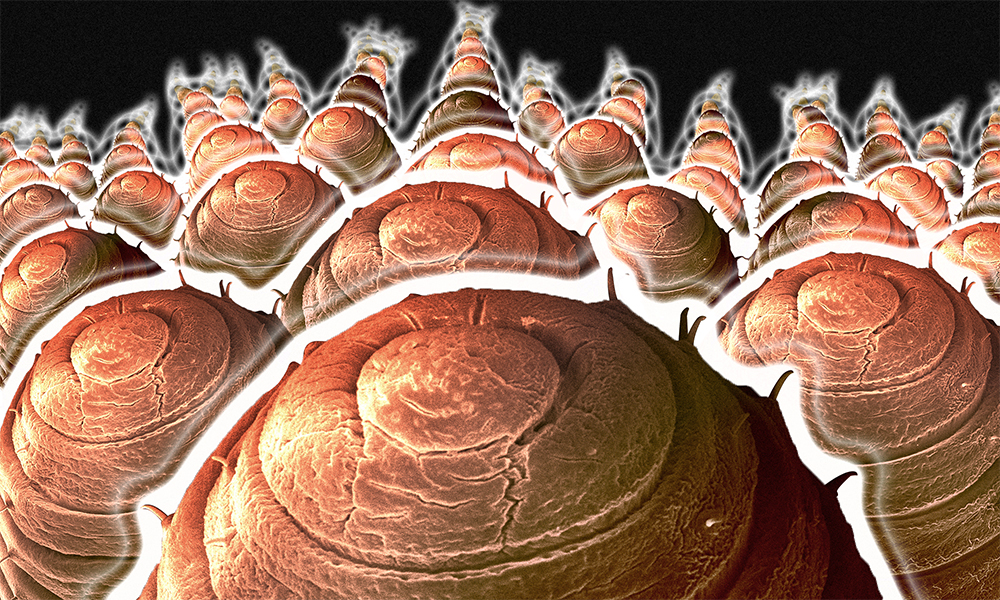

There is a place at the margin of our territory, an abandoned village at the foot of a precipice. It is said that many generations past, the village was sheltered by the cliff but then the wind changed direction. The way the wind blows today, the crescent walls of these old nests line up the wrong way so that anyone entering or leaving one would be caught exposed in the cross-wind and flipped or carried away. Now the site is overgrown as the forest reclaims the land. Here, sheltered in the rubble of a collapsed nest wall of rough-hewn stone, I found a hive of spineworms, tasty and nutritious, though care is needed in collecting them.

A good hive-site in one thread is often a good hive-site across broad ribbons of the weave, so I summoned all those of my selves that were nearby. In my own nest I told Mother, so that she too might come and bring others from the village. The apothecary would bring vapours to stun the spineworms.

I watched the hive and the comings and goings of the worms while more of my selves arrived each in her own thread. In many of these threads I discovered someone else already there watching the hive.

She raised her head and turned towards my self to speak. Begone, interloper. This is not your territory. Her length of five segments and immature colouration told she was of the same seed cohort as myself. The rhythms of her words that she came from the adjacent village.

I asserted precedence with bold flashes. We faced each other, cross-wind in the shelter of the undergrowth. My focus now was close on this thread, as hers would be. Throughout the many strands of the weave we converged and encountered each other at this spot, but in this thin strand alone would we resolve our dispute and accept the outcome through all the weave. That is the way we are taught to resolve disputes, the civilised way.

We began the ritual with sequences of flashes, patterns with no meaning. A wordless chant if you will, and our signalling synchronised. Together we raised our front segments from the ground, a trial of strength in itself. We swayed and chanted. She raised her second segment up so she towered over me. A boastful show of strength. I did the same, to fail to do so would be to concede. The wind pressed hard on my flank, threatening to topple me. My muscles strained to hold me up and keep me steady in the cross-wind.

Faster we chanted, and straining on the legs of our anterior segments we edged towards one another. I do not know whether she was pressing the pace or I was, but I felt an eagerness. It was almost as if we were a single mind, a single will. Only dimly was I aware of all my other selves watching her other selves waiting in a tense stillness.

This self, this thread, was all that there was.

My focus was upon that fine fibre of being, upon her, complete and singular. I felt the climax of the chant approach, and I saw the glint of my own ridges reflected in her eyes.

The chant ended and we both lunged. I managed to bring my head lower than hers, but she had artfully pushed herself sideways, upwind. I felt my defeat as her flank crashed into the side of my head and she let the wind take her and so me. I fell and could not stop myself as wind and inertia rolled me onto my side. In desperation, I twisted my rear segments, not to resist the roll, but to press it further.

The carapace of my head rang with the impact as it hit the hard ground, but I rolled, rolled right out from beneath my adversary, onto my back, up onto the other flank and onto my feet. I might have rolled further but for the remnant of a nest wall. I felt the sharp pain of a carapace cracking in my third segment.

I have never before or since felt such pain, for my focus was solely on that self, a singular body experiencing a singular pain.

A cracked carapace loses its strength and its weight presses and crushes the flesh beneath that it normally supports and protects. One leg was numb and useless and all the lateral eyes on that side were blind. I thought soon to feel my adversary’s mandibles bringing relief from that agony.

But the pain did not abate. I fought through it to turn my head and see.

She lay next to me, on her back, helpless. The victory was mine, and so the duty of the victor. No matter how hard, I had to finish the matter. Dragging my useless leg I twisted around and mounted upon her exposed underside. I pushed the tips of my mandibles into the exposed gap before the first segment and bit as hard as I could.

As the head rolled away, I released my focus, spreading myself again through the weave.

Well fought, the adversary said. The roll was a clever move. Daring. Her lights shimmered with admiration as we lay side by side in front of the hive. Is someone coming to aid you in your distress?

The pain of my injuries had faded, diluted as my focus withdrew from that strand. Even so, it was a relief when Mother arrived. Her ridges flashed with words of pride and a little regret as she came close.

Yes, I said to the adversary, speaking in gentle shades. But you flatter me. The move was not clever. Merely fortunate.

My relief came soon. That thread was lost to me as Mother’s head leaned over me and her kind, sharp mandibles penetrated the gap between head and first segment.

We talked while we awaited the others from my village. She was offspring of the weaver, a profession of high status both for its practicality and its symbolism.

One thread in every two we harvested the worms, stripping their spines and collecting them in bags of woven cloth. In the others we let them be, for they have as much right to the weave as any living thing.

The weaver’s offspring and I parted on good terms, I gifted her some of my allocation of the harvested spineworms.

That was the first time that I died so many deaths that I felt myself diminish. Once the shock had passed—of feeling my eyes go blind and my fluids boiling beneath my blistering carapace—I realised my thoughts felt foggy, my focus vague.

You will recover what you have lost, Grandmother said in a moment of rare lucidity. In my diminished state I found new empathy for her situation. Decline was all that remained for her as her deaths came faster. Her weave thinned and frayed, and with every day I found her sedentary form lying in the nest in fewer of the threads of my own lives.

In a thick cord, I too lay still in the nest. The glazed discolourations of my carapace would be with me for life in those worlds, but the burned and blistered flesh beneath would heal in time, the lost eyes would grow back.

You will recover what you have lost, she said again, perhaps in a different thread, sometimes it is hard to tell.

Tell me a story, I said, though I doubted her focus would hold enough.

A story? What story? Shall I tell you of how we learnt to build with cement rather than rough stone, of how we learned to work metal? My grandmother lived folds of the weave where the visitor gave us this knowledge, and much else besides, but in these strands where we live our many lives we were so few and stretched so thin that only fragments of the knowledge came to us.

Why so few?

She lay uncommunicative for long moments. An intermittent flickering of her ridges, was the only sign that she was still conscious. I thought her mind had drifted away again following its own shadowed paths, when her words shone bright in my eyes. Life is hard in the ribbons of the weave that we know, and we are few. When I was a five-segment youth as you are now, my grandmother told me it was not so elsewhere.

But how? How can the worlds be so different, is not the nature of the physical world the same in all the weave? Even as I spoke, I recalled those dying worlds of cold and heat and strange skies.

Her ridges rippled in the soothing colours one might use to calm an infant. A grub in a tree may eat one leaf in one strand and do no harm, but in another strand a different leaf is eaten and brings a rip-storm on the other side of the world.

It was a story we all learn as infants, of how small choices can have unpredictable effects in different strands of the weave, leading to wild divergences between the worlds.

Perhaps, she continued, if it eats both leaves, the wind will change direction.

I shivered with fright at the thought of the abandoned village. The wind had changed in threads ancestral to all of the weave that I lived. So many must have been caught in the crosswind and died, and the survivors would have been diminished. This was her story. We were few and stretched thin because the wind changed direction.

She was singular as a stone that is kicked in one thread and knows not in the remainder of the weave. That’s what they said.

Who? I demanded, but her light faded, her rambling slowed. A last flicker, that might have been so far away, or it may have just been the random flutterings of her fading mind.

That night her hearts failed in many of the threads that remained to her and she lost the power of speech entirely. It is in the ways of the worlds that the elderly fade so, not all at once across the weave but stretched ever thinner along fewer and finer warps.

Grandmother continued to decline. She now lived in only the sparsest, thinnest strands, in a state of total senescence, eating only when food was placed between her mandibles.

The weaver’s offspring, my former adversary from that day in the abandoned village, was now a familiar sight in our own village, and I in hers. Now in new adulthood, she was herself a weaver. Mother said she waited for the seeding of the next cohort, confident that the weaver and I would sow each other’s seeds. But since that last conversation with Grandmother I had little confidence in planning futures. We will see when the season comes, I told Mother.

More than once as I lay in the nest at night I saw a light flash across the sky. It was not a common occurrence, but enough to bring back memories of Grandmother’s incoherent ramblings of things above the clouds, and of what I had seen in dying worlds. Then the day came, where a light crossed the sky in the middle of the day. It did not flash across in the time it takes to blink twice, but slow and bright, falling slower and brighter until it hurt to look.

It seemed to descend from the sky in the direction of the abandoned village, and it did so in all of the weave that I knew.

It had curves and edges unlike anything we had seen before. It’s surface held a sheen like the carapace of a new-hatched infant and bristled with odd protrusions. In length it would measure from my head to my fourth segment, but it was twice as wide and high as myself. Four thin legs spread wide from its underside held its belly clear from the ground. I wondered at the strength of those thin spars.

Is it a living thing? the weaver asked.

I think not. My eyes were drawn to the edges, the angles of the protrusions, some of which had that hard brightness of metal. I believe it is a made thing.

We will learn little by looking, she said, and in a thin strand she crawled from the cover of the trees and headed straight towards it.

As she approached within a dozen body lengths, some of the protrusions erupted into bright lights, dazzling my forward eyes.

I am blinded, she said, lying next to me in another stream.

Keep going straight, I said, squinting beneath folded ridges against the brightness.

She blundered straight forward until her mandibles struck the thing. She opened them wide, stepped forward once more and closed her jaws on the object, the point of her mandible slid until it caught on one of the protrusions.

Very hard, she said. I don’t think I can…

As she spoke, the thing’s surface buckled as the point penetrated. A jet of vapour burst from the puncture, then all was consumed in bright fire. All: the object, the weaver. The whole space between the wood and the cliff was lost in bright flame. The ridges folded down over my eyes, saving something of my forward vision.

What happened? said the weaver next to me.

I had no answer at first. I feared the heat of the flame would set light to the forest where I lay, but the heat faded almost as quickly as it had come. I uncovered my eyes and saw a blackened hollow. Of the object and the weaver I saw at first no trace.

I crawled out of my shelter into the open, across the blackened ground, and as I did, I saw with my eyes and felt under my feet hard, sharp shards. Pieces of the weaver’s carapace, fragments of blackened and twisted metal.

I was right, I said to the weaver as I continued my search. It is a made thing.

I searched the blackened crater to see what I might learn, and I rested at the forest edge with the weaver to watch the object and see what we might learn.

The side of the object opened and something came out. It balanced precariously on two legs, upright. It had such a curious head, a smooth, white shining carapace, and what looked like a single great eye filling the forward face. It’s movements were rapid, but clumsy. I expected it to topple to the ground and smash itself to pieces. It seemed to struggle also with the wind, even in the shelter of the cliff.

It busied itself with a number of objects it extracted from the interior of what I now began to think of its nest.

We watched, mystified, captivated, until a flat plate it had placed on the ground angled towards us and erupted in light. Not the glare that had dazzled me and blinded the weaver when she approached in that destructive thread, but the patterns of the glowing ridges of a face.

I am blind, it said. Then, Keep going straight. Very hard. I don’t think I can. What happened?

It was repeating our words, but only the words we had spoken in this thread, though it must have seen what we said in that other strand.

I picked a few strands and crawled out from the shelter. I stopped just short of the distance at which those dazzling lights had started. The two-legged stranger edged back a little, but stepped forward again when I stopped.

Hello, I said. Goodbye, I said in another thread. In another: Singular as a stone. Whence came those words? Distracted, I almost neglected to watch the response on the panel.

In each thread came the same words I had flashed.

This is madness, I said to the weaver, what can she hope to learn by responding the same way in every stream?

Patience, she said. Perhaps she waits for a different response from you.

I paused for a moment, and I remembered my first meeting with the weaver. Somehow, the memory of pain of that meeting was diminished. It was the thrill of the dance that I remembered now. Join me in a strand, I told the weaver, just a single thread. Let us see if we can evoke a more meaningful response.

She did as I asked, and I flashed at her the beginnings of the chant, of the challenge. She understood my intent and joined me. We faced each other, chanted, raised our forward segments. The stranger backed away as we swayed—in truth the wind was feeble here in the shadow of the cliff, scarce enough to topple either of us, but this was more a show.

In another thread, I chanted to the stranger instead. You will have to tell me how she reacts, said the weaver.

Our shared chant reached its climax. The weaver feinted towards me, a low and slow lunge, and I pressed the advantage, my mandibles scissored, and the head fell from her neck.

My solo chant reached its climax, I lunged forward and closed my mandibles around the protrusion at the apex of the stranger’s body, which I took to be its head, if it had such. It was easily severed and fell to the ground and its carapace cracked. A dark liquid pulsed from the cut on the body, and oozed from the severed head.

I lowered my head before the stranger, offering her the opportunity to sever my own head, should she have the means to do so.

The stranger showed no reaction anywhere in the rest of the weave. I watched from the forest with the weaver as the panel simply repeated our earlier conversation. Even where I exposed the join between my head and first segment, the stranger stood mute and impassive.

The only reaction came from the weaver’s death. The stranger hurried with its clumsy two-legged gait and climbed into the opening of its nest. I waited to see if it would emerge again. I waited long and was about to give up when the entire nest of curves and edges and protrusions vanished, looking like it had twisted away in some unimaginable direction.

It did the same where the stranger lay decapitated before me. The nest just vanished. The weaver saw too, for which I was grateful. I feared she would not believe had I needed to describe what I had seen.

Still, these were narrow threads, and the stranger and her nest remained in a broad ribbon of rich and branching warps.

I struggled to comprehend the meaning of this stranger’s reactions.

I observed that throughout the thickness of the weave where the stranger was present, she acted in the precise same way, save in those where I or the weaver had chosen to act differently, as if she had no power to manipulate the weave of her own volition, but only to react to the circumstance of the thread in which she found herself.

She attempted to communicate with us. Her lighted panel shifted from showing faces that repeated our words, to patterns far simpler. Numbers of dots, lines and geometrical shapes.

A game. I said what I saw, she repeated my words. By varying my answers in different threads and seeing her responses, I saw the patterns, I saw what she was trying to do and I learned quickly.

She learned slowly. Every lesson, every word, every phrase, she had to learn anew in every thread separately. As my responses varied, so did hers. Her progress was faster or slower in one thread or another. In those where her progress was fastest, I learned the next move in the game and in other threads I was able to respond to each problem as soon as, or before she posed it.

Days passed like this, and at the end of each day as the clouds darkened she retired to her nest and I walked back to mine. The weaver helped me during the long days, fetching me sustenance and pressing me to eat when, in my wide and deep focus, I would forget.

In time, many days, the stranger was able to display simple sentences.

I go. I return in three days, she said to me one day in a fine strand.

You go. You return in three days, I said to her throughout the weave.

How do you know? she said, in those threads where she had learned enough to understand.

Wisdom is in the weave, I replied, but I think the meaning was lost on her.

I crawled back to my village, to the nest I shared mostly with my mother. The next day, my strength was recovered enough to focus and tell her what I had seen, what I had been doing these last days when she might have expected me in the forge.

I looked to that sad corner of the nest where Grandmother used to lie.

You come from above the clouds, I said to her.

Something new, she carried a speaking panel on the front of her carapace. I come from above the clouds. Another world.

I do not understand, I said. The worlds in the threads are not above the clouds, and we can not travel from one to another. We simply experience them.

Most times she would answer very quickly, I had the sense that her thinking was fast, like her movements, but it lacked breadth. I waited.

I have not words to explain, but yes, I come from above the clouds.

We talked, we misunderstood, we learned. Eight days she stayed, then three days she went back up above the clouds. This routine repeated many times in many threads. In time we began to comprehend each other in small and mundane ways

In a few sparse threads she never came back, and in one, as her nest descended on its column of fire, the wind swirled around the sheltering cliff and smashed the nest against the unforgiving rock. It erupted in fire as it had that day that the weaver’s mandibles had penetrated it.

I told her. You died coming here.

Her response came quickly. I live yet.

I watched your nest descend, I saw it taken by the wind and shattered on the stone. You must have been killed.

Her head moved, angled to one side a little. It is a mystery to me that you can see this. We know that the world we see is one of many branching possibilities but we can never see those other worlds.

The broad chasm in my understanding yawned before me. You feel no diminution from the death of your other self?

That was not me. That was someone who shared a past with me, but moved on to another fate. I can die only once. She died.

I absorbed this. To experience the weave was the very definition of life. Even the worms that burrow in the ground retreat in many threads from a threat in one. I considered the possibility of death in a single strand being a final end to a living thing. I reflected on what I had done on the day the stranger arrived.

Once before, another who shared your past has died here.

The panel she used to speak remained dark. Her curious head straightened and tilted to the other side. I fancied I saw movement within that great eye when the light caught it.

I could not but explain further, though I feared her reaction so I spoke my thought in only a thin strand. I regret. I killed you, I said. I meant no harm by it. Death is a small thing for us.

Have no regret for me. When I am dead I am gone, but there is another who waits above the clouds for whom my end would have brought pain.

Speak to her of my regrets.

Through this eye she sees all that I see. The stranger touched a projection at the side of her head. She understands as I do. Death is a small thing for you.

My lateral eyes detected a motion. The branches of the trees furling themselves, wrapping tight around the trunks.

She spoke again. But is it always so? Is death always a small thing for you?

A storm is coming, I said. The trees sense it across the weave. I said it to her in all the threads, not just those of this more intimate conversation.

I must leave, I will return after the storm, she said many times, everywhere she had gained understanding, and hurried back to her nest.

I felt the force of the wind pressing on my carapace. The stranger clambered into her nest.

She stood still before me. I must know, before the storm comes. I must know is death always a small thing for you?

No, it is not always a small thing. Too many deaths and we diminish, we lose our selves.

I live one life, I have one past, but we know there are many worlds. She hesitated again. I struggle to find the words, but the ground on which we stand moves. Over many lifetimes it must move in the same way in every world. Are the storms stronger, more frequent, in every world?

The trees now were furled tight, but the younger growth, the littler plants with shallow roots could not withstand the rising storm. Here in this sheltered spot we escaped the worst, but to either side I saw trees and branches and small animals flung into the air and carried away.

In thread after thread, throughout the weave, the stranger’s nest performed its mysterious convolutions and was gone. But here, she remained awaiting my answer.

Everywhere. Throughout the weave. The world has died many times, but there is no strand of mine that does not suffer storms or cold or heat.

She stepped forward, this tiny frail creature, and rested a forelimb on my extended mandible. I regret there is no more I can do.

She turned to return to her nest, but a flurry of wind twisted around the cliff and caught her mid-stride, sending her crashing to the ground before me.

What do you mean? I said, but she lay face down, straining with upper limbs to push herself up. She would not have seen my words. As gentle as a mother with a seedling, I closed my mandibles beneath her and lifted.

I released her, and she stumbled forward and rested her back against the rock face.

The wind is changing. The weaver’s words came to me from another thread. I widened my focus and felt the force of it. We clung to the ground. A heavy branch ripped from an ancient tree flew through the air towards me.

We lay huddled tight against the crescent wall of the nest, Mother and I, latched onto each other like three-segment youths as the wind curled around the end wall. No way to leave the nest without being torn away.

Throughout the weave, the wind was changing. In some threads already a full rip-storm was tearing the trees from the ground and scouring deep scars in the soil, the clouds above lost in the haze of wind-borne dust and rock.

I searched to focus again on the stranger, but it was a thin thread, and I felt my deaths building, my mind diminishing, my focus weakening.

I will die here. Her words brought me to her. She rested against the cliff, her single great eye and speaking panel facing me. The wind here too was turning and strengthening.

Are you injured? I said, but before she answered I saw her nest. The turning of the wind had exposed it to the rising storm. It lay on its side, trails of white vapour pouring from it, torn into thin streamers by the wind.

I regret, I said, But if it be some solace, only in this thin thread. You departed safely elsewhere.

She rested motionless, her panel dark, and I wondered if she had already died from some injury sustained in her fall.

I regret, she said, that I can offer you no such comfort. Your world is dying. I think it must be so in every thread as it moves further from the light that warms it.

I sensed the truth of her words. So much had I seen, and now I felt my weave thinning and fraying moment by moment.

If we had found you sooner we might have been able to help, to make you another home above the clouds, or to teach you… She raised her forelimbs to the front of her neck. There is pain. I don’t want to die a slow death as my air runs out, she said. This will be quicker, and we may see each other with our own eyes.

She did something and a puff of vapour rushed from her neck. She lifted away the carapace from her head and placed it carefully on the ground beside her. I saw for the first time the true face of the stranger.

On the front of her fragile form, the speaking panel glows with a last word to me:

Goodbye.

She met my gaze with her two eyes, and then she died.

Know also, that your kind has been here before, long ago in distant threads. Only now do I understand my grandmother’s words, of knowledge brought from above the clouds in distant threads and a visitor singular as a stone.

Perhaps in distant folds of the weave our kind lives yet with yours, above the clouds.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of In The Weave on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)