A Deer's Inheritance

C. Owen Loftus

It’s important you know he was never called that. His family called him the sound hungry children made at seeing he’d caught an animal for them to eat, or the grunt of a stifled wretch when the smell of open guts overwhelmed the one holding the carcass up for him to clean. Sometimes, on sacred days, they just called him by an expectant silence around a bonfire until he burned the animals’ eyes and genitals. Asa’s name was the same word as death and springtime.

There was a boy, too. He thought of himself as a man, but his limbs were still the wrong lengths and his face was covered in red spots. He was shy, and never married. He was too young to have very many names. I know that no one called him Eze.

Once, after laying in silence with Asa in a tree for five days, waiting for an animal to pass underneath, the boy said,

(and remember these words are both misleading and unreal, all at once)

“I don’t believe in souls.”

Asa twitched in an automatic gesture of frustration, but nothing scattered in the bushes, so he measured his eventual response.

“Why not?” he asked.

“I can see everything,” Eze said.

“Hmm,” Asa grunted. Then, “Would you like to see one?”

It surprised Eze that the old man could offer it so easily.

“Yes,” he said, and blinked slowly.

“Wait,” Asa said, “for the deer. I’ll let you pick the one whose soul you want to see.”

Eze could hardly call this unreasonable, so he settled back into his furs.

It took only four more days before their game came. Three were fawns, and three were does, but one was a buck, and Eze thought its rack looked ornate and violent. He pointed at it in a flickering, near-invisible motion. Asa saw it, drew his bow, and shot the animal in its haunch.

The herd scattered, and the men packed to begin the arduous work of following the buck’s trail. Eze used the time to mutter at the old man’s poor aim.

“If I wanted a heart shot, I’d have shot at the heart,” Asa said. “It takes more than killing to see a soul.”

They walked a long ways before finally finding their quarry. He was curled against a fallen tree, shivering in the dusky gloom. Eze drew his obsidian knife from its soft leather pouch, but Asa placed a heavy finger on the blade’s tip and pulled it down.

“Seeing a soul must take at least a little killing,” Eze said.

“Don’t worry,” Asa said. “The buck will die.”

“When? What are you doing?”

The old man knelt beside the buck. It stirred, but was too spent to stand. In exhaustion he let Asa pull the arrow shaft out of his leg, and dig the head out from his muscles with his fingers.

“There’s a difference between dying and getting killed,” Asa said. His tone was serious, but he wiggled his eyebrows and smiled impishly.

Eze wore sourness like facepaint. He snorted and folded his arms. “This is a joke,” he said.

Asa sighed from his mouth, and Eze tasted his sour adrenaline on the air.

“No,” the old man finally said. “I’m sorry. This is important, and I want you to understand it.”

Eze snorted again, from impatience.

“We’ll take the buck there,” Asa said, and pointed upwards at something neither could see through the trees. “There, when he dies, you’ll see the soul leave him.”

The boy grabbed the old man from behind and used the surprise to put him in a chokehold. With his free hand he pulled on the black and greying beard.

“This is strange,” he said, “and complicated. Promise to me that I will see his soul.”

Eze hated the crack in his voice. He wiped sweat from his face with his arm, and suddenly was on his back, the old man’s forearm pinning him to the ground at the throat.

“I promise,” Asa said. Eze gagged at the pressure on his windpipe, and the old man laughed and pulled him to his feet. But he quieted when he saw the solemnity in the boy’s expression. “Eze. I swear by the deer and their meat and their hooves and their bones.”

Eze blushed. It was a strange, consequential thing to swear by.

“Thank you,” he said in the wavering, vulnerable secret voice you can only show those you trust.

They built a small fire against the dark. The buck didn’t move when they gathered sticks, nor at the sight of the red flames taking root in them. Neither man spoke into the growing darkness, only chewed their greens and jerky in a watchful rest. Asa touched the boy’s elbow, and at the familiar sign Eze let himself drift into sleep.

When he woke, the buck was unmoved and panting in a pool of blood. It coated his hindquarters in a visceral glaze and shone in the early light like earthenware jugs filled with fresh water. Asa knelt in front of it, one hand on the animal’s neck. Their muscles were hard, and both their eyes were bloodshot.

“Do as I tell you,” Asa said without turning. “Heal him.”

The boy blinked away his fading sleep, then slipped into the shade between the trees.

When the boy was gone, Asa prayed. He didn’t speak in a whisper, but his tone was hushed and private. “You are alive,” he said. “You are here and see me, seeing you. Will you run? Your soul is in your skin.”

He prayed until Eze came back in the afternoon, carrying what he’d found foraging. At the sound of his footsteps, the old bent man over double and drank from the pool of congealed animal blood around his knees. Then he continued as before.

Eze chewed the leaves and spat them into the buck’s wounds. Aside from the tear in his haunch, now stretched wide from the chase, the shins of both his forelegs were broken. The buck mewed plaintively when Eze wrapped the exposed bone in poultices.

Eze knew Asa would pray for four days. It was the old man’s custom. So he settled into his orders, and turned the clearing into a little camp. He twisted his tunic into a rope, dipped it into a nearby stream, and held it between Asa’s teeth as if trying to gag him. The movement of the old man’s prayer squeezed the water from the cloth and let Asa drank without stopping. For the deer, Eze collected the plants that were most full of life and buried the broken arrow head under piles of their leaves. He chewed roots until they nearly slid down his throat, then spit them into both their mouths so the ritual wouldn’t break for anything as mundane as the need to eat. He cleaned them, and shaded them, and wanted very badly for Asa’s prayer to be finished.

But he was too young to maintain any single feeling very long, so on the second day he occupied himself by tracking what he could of their hunt. He found a gnarled log on the northern side of the clearing, half rotted with mold and buried under the fronds of an enormous fern. The log was split in the middle, and the breakage was flecked with blood and splintered bone. The buck must have run into it at full tilt, not knowing it was there. It was that blow that snapped his legs and sent him tumbling into the tree that he still lay beneath. Eze pressed his lips together and quelled the sympathy pains the discovery sent shivering through his calves.

On the third day Asa’s voice wore away until there was no sound behind it except the harsh rattling of his breath. Eze did his best not to pay too much attention to it. He believed knowing what Asa prayed would be intrusive and rude, or worse. So during the last night, to distance himself from the murmurs, Eze left the camp to watch the stars from a distant tree.

Eze shrieked, the first real sound in the clearing in days, and ran to him. The old man was barely conscious. The boy rolled him onto his back and slapped his face, but Asa’s eyes skittered at nothing behind half-closed lids. His skin was pallid and hot as rocks in the sun.

The boy pulled him to the bed of moss and furs he’d made next to the fire and used his knife to cut off the old man’s clothes. Then he filled his water pouch and poured a cool stream over Asa’s burning body. He did this til the sun came up, and on through the day because the old man only get hotter in the light. The boy tried to cool him, and sometimes cried, because, as you might have guessed, the old man was his father, and he was frightened of losing him.

When night fell Asa’s body began to shiver violently, so Eze wrapped him in the ruined shreds of his slit tunic and the bedroll leathers. The old man sweated so profusely that his skin glowed in the starlight. It reminded Eze of the blood on the buck’s haunches, and he stood up because the memory gave him a target for his unspoken fears.

He turned to the deer and called it a hiss of derision. The buck only shook his antlers, weakly. So, Eze called him a shout of promised violence. He ran to the buck and grabbed his antlers, intent on shaking the animal’s head to pieces, and the horn fell apart in his hands. Eze called him a scoff of roiling disgust that rose from his belly, but then realized that all that had happened was the shedding of a little velvet.

“Go to a tree then, and tear it off of you,” Eze said. When the deer didn’t, he called him uncontributive, which to the boy was a great insult. “Get up,” he screamed. “Get up or I’ll kill you.”

He grabbed the dagger from his belt and held the point against the deer’s swollen belly. The buck didn’t move, only rolled his eyes, and rattled his head, and Eze understood the buck’s words clearly.

“I can’t, my body is broken,” the buck said.

Eze growled, then padded on his silent hunter’s feet to the animal’s flank. The ground showed him that the hooves hadn’t moved since their blood had softened the soil. The buck’s back was split by its fall into the tree. It would never walk again.

Eze went back to the fire. He took a string of jerky from its pouch, and gnawed at it while he thought about the new words he’d learned.

After a time, he went to gather more wood for the fire. But the last stick he held at one end and carried to the buck. He used it to scrape at the bloody velvet. The animal, though frightened at first, soon pushed his head eagerly against the rough wood. Blood splattered from his horns while sparks flew from the wet twigs popping in the fire. When it was done, the boy patted the buck’s neck softly and said what he thought the old man might say, if their situations were reversed.

“The tree will come to you,” he said. He whispered it, because his throat was tight.

The buck closed his eyes and let out a long, calm sigh.

Eze understood, and said it back to him.

During the day, he sucked the pus from the buck’s wounds and spat the maggots into the bushes. At night, he banked and stoked the fire to match the old man’s changing fits. When he could, he caught the crickets that jumped on him in the dark and roasted them for their meat. They had precious little meat, but he had precious little else to do.

At dawn on one of those days, Asa spoke. Eze thought at first that it was to him, and it made his heart leap, but soon realized the old man said nonsense directed to no one. He raved about animals and jumping and how it felt to have sex with a woman and see your son came out of her. Eze spoke back at first, though their conversations made no sense to him, but his replies became more sporadic as he slowly realized the old man couldn’t even hear him. By the fifth dusk, he just watched, and responded to Asa’s cries for water in silence.

The buck grew quiet with him. It lay calmly on its bandaged legs like a cat, and never slept. Eze wondered if the animal had lost its fight, or just its fear. During Asa’s quiet moments, the boy sat next to the deer and tried to learn more of his words.

He stood next to Asa and stared at the old man’s face until the sun was exactly overhead. Then, with a half extended hand making a silent gesture of apology, he slipped away.

He had to walk a fair distance to find even a few things to eat. He’d emptied the immediate circle of forest of good herbs days earlier, and they’d camped there long enough that the birds and small things had learned to keep their distance. It took longer than he hoped.

When he returned, a bundle of leaves under one arm and a few berries clutched in his palm, it was nearly dusk. The fire was dead, probably doused by a small drizzle that hadn’t reached him, and the camp was riddled with rot. Two ravens scattered from the buck’s back, beaks dripping with stolen blood. The old man’s face and beard was covered in vomit, and his nose was blue.

Eze ran to him, and jammed his fingers as far down the old man’s throat as they would go. He felt and pushed, heedless of the tracks his nails left in his father’s mouth. When he found the lodged chunk of bile, and pulled it out between pincered fingers, his first reaction was shock at the amount of poisonous green that streaked the mucus. But then Asa coughed, then retched, and fell silent again, and the boy’s thoughts focused on only the old man, on his breathing and his heart beating in his thinning chest.

When he was finished and stepped back, the boy’s own heart screeched because he saw Asa’s skin dripping with new wounds. But on inspection it was only the berries, smashed against the sick man’s bones in his panicked caregiving. Eze pounded his fists against his legs, and threw the little food that remained untouched back into the forest, as hard as he could.

There was little to be done. They could go home, but it was several days’ journey in the best of circumstances. Eze could go alone and return with supplies and help, but he felt sure the old man wouldn’t last that long by himself. Or he could leave alone, and not come back, and try to live with leaving his father to die where no one remembered his name.

His father would die, Eze felt sure, unless he could find a way to fill the old man’s belly and wake him up from wherever he was dreaming.

There was a clatter of antler on wood, and the boy realized how easy it was to save them both. He turned, and looked at the buck’s muscles under its skin, at the tendons that tugged sharply through its neck. He imagined the taste of them as he chewed them over days into nothingness.

His black obsidian knife was still in its pouch at his hip. He’d never hunted this way before, it wasn’t his way to do so, but a hunt had never been this way before. He’d cursed the three of them from the start of it with his stupid questions. It had all gone too perfectly badly. They’d waited so long for the buck that the men had no strength to spare. They’d chased that particular buck to this particular place, where it would lay in state of painful undying and borrow strength from them all until all were spent.

The three were trapped by the way their bodies were tied to the others’. The man couldn’t live without the boy to feed him, and the boy couldn’t save the man while the buck remained alive. Still, the deer’s safety was sworn, by the same man it killed by slowly dying.

The boy felt as if an unseen but enormous snake was coiling them more tightly by the moment, had been wrapping around them for weeks, but so slowly that he hadn’t seen it until it was too late. The tautness that suffocated them needed to be released before they strangled. If he dared to snick the thread, the balance would tip, and the others would be free.

Eze drew the knife from its pouch, watched the firelight glitter along the bowls its carving had left along the blade, and then put it away. Instead, he found the old man’s knife in his ruined things. This was a knife that could sever the things that bound them to this spot.

But he stopped, a pace away from the buck. It watched him and followed his movements with his ears. Eze’s curse was so clever, so ingeniously laid, that even now he needed the old man to end it. Eze couldn’t kill this buck, because he’d never let himself hear what the old man said before he’d slit their throats.

It’s not important, the boy thought. The deer will be dead. I need its meat, not its soul.

But he looked at it, tried to see more deeply inside it than he ever had, and realized that the animal had done nothing wrong. It was his, Eze’s, fault that they were here, and that his father needed this death to live, and that he needed his father alive or he would die, too, because the boy couldn’t bear to do the things that would save himself. He’d already killed his father, whether or not he also murdered this buck without even performing its prayer.

He fell heavily onto the ground and leaned back against his hands, the wrapped handle of the knife cutting off the circulation in his palm.

“Do you have a family?” he asked. But he knew the buck didn’t understand. He tried again, but this time said it in words that sound like a small hand tucking behind enormous velvety ears to scratch gently. The buck said a word Eze didn’t know but sounded like the quiet breath of someone who believes they will always feel as safe as they do in that moment.

“You’re not the reason my father will die,” he said. “I can’t be the reason you die, too.”

The deer snuffled, a wet sound that left droplets of moisture on Eze’s hand, and laid its head down in the dirt. Eze turned in his spot, and leaned back against the buck’s torso. His skin was warm and his fur soft.

The buck’s breathing, measured evenly by Eze’s rise and fall against him, slowed. From the corner of his eye, the boy saw the buck’s eyes finally close. For the first time since they’d met, he was asleep, and in a moment, the boy was too.

When he woke up, curled into the buck’s belly like a puppy to its mother, he again picked up the knife and carried it to his father. There, he cut into the flesh above his own arm until a rivulet of blood dripped strong and freely off his fingers. He dripped this blood into the old man’s mouth, as a trade for the deer blood the old man dearly needed and the boy was unable to provide.

“What is this?” he asked, and Eze jumped at the sound. The boy scurried to him and began to fuss; re-tying wraps, stuffing his pillow, tracing his bruised knees with gentle fingers.

Asa winced at the attention, but was also warmed by it. When he felt strong enough to sit up, he looked into the fire and let Eze look for little things to eat.

“I thought you were going to die,” Eze said, gasping from exertion. He’d found a single tadpole that made its way down the stream to grow legs in the eddy by their little camp, and worn himself out chasing it. He sweated while he roasted the little half-frog over the fire.

“I am,” Asa said, and Eze shot up in a start and stared at him with a wildness that filled the pits of his eyes with black.

“But you’re getting better,” the boy said, and moved to hit Asa playfully, but stopped when he saw how frail the old man’s muscles were, how much of his strength it took to sit up.

“I still feel it coming,” Asa said. “I’m too old to pray. I wasn’t before, but now I am. I went too long.” He coughed, then swallowed a gulp of water from his pouch.

Eze looked terrified, and then angry. “Why didn’t you stop?” he said, loud enough to wake the birds nesting above them.

“I don’t know,” Asa said. “I’m sorry.”

The boy dropped in a squat and turned his face to the fire.

“I didn’t want to be too old,” the old man finally said.

When Eze started to cry, Asa crawled to him and put his hand around the back of the boy’s neck. He called his son by his first name, the shooshing purr that soothes a newborn who fears they are alone.

“Let’s go home,” Eze said. “You should be there.”

Asa looked at the sky. He followed the ridges of the nearby mountain where they cut into the sky and hid the stars behind it.

“No,” he said. “I want to give you what I promised.”

The walk wasn’t far, but it took them a long time to make it. Asa moved on his own but tired very quickly, so they covered what ground they could each day and camped beneath the trees. On the fourth afternoon they found a warren of little brown things and spent the rest of the day catching them and cooking them and laughing in relief.

The bath was abrasive and revealing. All three were much thinner than they’d started, but Asa’s shrinking musculature was riddled with sores and boils that grew in his joints. When the old man’s arms shook too badly to continue, Eze finished cleaning him. Then he cradled the buck and carried him into the pool, half submerged, so that Asa could wash his fur and hooves.

“You did a good job with him,” the old man said, and Eze smiled sadly.

“We became friends,” he said.

“That’s good,” Asa said. “You can’t the see the soul of something you don’t love.” He pulled the strings of filth from the buck’s fur and ran a finger over the arrow wound in his haunch. The cut had closed well, but left a pink, glistening scar. “You did better than you had to, even. I’m proud of you for that.”

“I’m sorry,” Eze said. It took them both by surprise.

“For what?” the old man said.

“It’s my fault he has to die, because I’m the one who chose him. I just thought his antlers were pretty, and that meant his soul would be beautiful.” Then he glowered into the water. “It’s my fault that you are going to die.”

Asa rinsed the buck’s damp fur and poured a little over the boy’s head.

“We’ll die,” Asa said, “but we’ll be seen first. There are worse things.”

They finished their ritual, ate a meal while their tunics dried, and then found the trail that climbed up the rock to the mountain’s peaks. They left everything else behind, tucked into a boulder’s niche as a token protection against the birds.

“Let’s stop,” he said, “and go back.” When Asa turned to meet his eyes, he said, “I release you from your oath.”

Asa’s frame shook in the bitter cold.

“I’m not doing this because I have to,” he said.

“Please stop,” Eze said. “I don’t want this anymore.”

Asa backtracked to him, tugged on the boy’s wispy chin hairs, and took the buck from his shoulders.

“I don’t want to either,” Asa said softly. “But I choose it.”

He hoisted the buck to rest securely on his neck, and began the walk up again. Eze gawped a moment, then chased after them, calling both something wordless and in pain. At the sound, the buck took fright. He threw his neck and attacked Asa with his brittle hooves. The old man stumbled, then fell to his knees, and the buck fell into the snow. He found purchase on the slippery rock despite his twisted legs, and dragged himself away. He looked back at Eze, without stopping, and tumbled headfirst off a cliff.

Asa grabbed the buck by an antler and hoisted him onto a flat place. It only took one hand–the animal was emaciated and light.

The stench of death made Eze’s eyes water. There was no magic here, no secret thing to watch fly away. It was only a crippled deer corpse, already dripping with excrement and parasitizing flies. A frightened animal whose eyes were clouded with burst vessels and hooves caked with piss-stained ice.

The old man let the boy mourn, then touched his elbow.“It will be dark, soon,” he said. “And I don’t have another day inside me. Will you come?”

The boy rubbed the buck’s antlers between his fingers, and nodded.

They found the trail, and began again to climb. The setting sun turned the air red as the veins around Asa’s eyes. The shadows of their hands as they dug into the snow for purchase turned it purple sure as if they dripped with oncoming dusk.

With still more than half of that last climb left, Asa fell. His body clenched in rippling spams. Eze leapt to him, brushed the frozen dirt from his face, and put him on his shoulders. Just ahead he found a small cleft, flat enough and sheltered from the frost that blew into their eyes. The boy laid him there, and rubbed his father’s hands until they softened from their claws.

“We’re there,” the old man said.

“We’re not at the top,” Eze said. He had to shout to hear himself over the whipping wind. “I can carry you.”

“It’s too late. It has to be light to work,” Asa said. His eyes were turning glassy, and they reflected the dying pink of the sky.

“But how,” Eze shouted, “do you know your soul will come out before then?”

Asa took his obsidian knife from its pouch at his hip. “Pray for me,” the old man said.

“What? I don’t know how. Answer my question.”

The old man put the knife into the boy’s hand, and gestured at his throat.

“You’ll learn,” he said.

Eze blanched at the black blade, and pushed it back.

“You’re still alive,” he said.

“That’s it,” Asa said. “That’s always the first prayer.”

He coughed, until Eze was sure it would last til they both were dead and frozen on top of the mountain. But he did stop, and then he sat up, fighting against his atrophied muscles as they rebelled against him. He knelt, facing the dying sun.

“Hurry,” the old man said. “Please. I want you to see me.”

Eze heard the pleading, and it sunk into him. His father had prepared him for this moment by showing it to him a thousand times, through the deer and the elk and a single crippled buck. The old man’s voice was empty from his labor, and in it Eze heard how desperately his father wanted him to understand.

So he didn’t hesitate any longer. He let the knife glide through the old man’s throat. The muscles parted and the animal life poured out of its jug and onto the ground. The cut cords bubbled at contact with the air.

“Look,” the old man mouthed without sound, and the boy did.

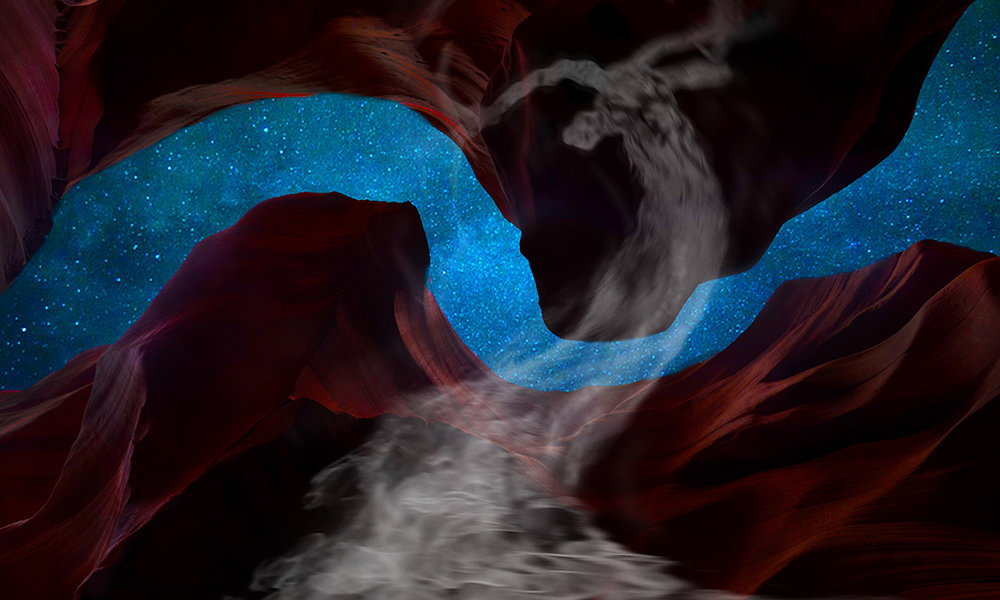

From the clean pool of his father’s heartblood rose the silver smoke of his soul. It curled against the air like a baby struggling to break its birth sac.

Asa steamed into the gloaming light of the first star long after his body stopped breathing.

Eze watched him fly, then knelt beside him in the same pose. He touched the elbow of Asa’s remains, which were frozen in their kneeling, and let the last sunlight wash away the old man’s remnants. He bent double, and sipped at the pool of blood around his knees.

When it was truly dark, he prayed, as his father had taught him. If you heard it, though you wouldn’t know the words he said, you would understand.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of A Deer’s Inheritance on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)