Balk

Lucy Zhang

I’d seen it happen while swimming two years ago. While I flung my arms forward like propellers in exhausted, half-hearted freestyle strokes, my red knotted-cord bracelet slipped off my wrist. I wasn’t supposed to take the bracelet off because it was my zodiac year, the misfortune-filled Ben Ming Nian; but as I dove to catch it, the water warped, sucking the bracelet into a whirlpool of gray and chlorine.

Mom insisted the lifeguard search for it, but he said it must’ve been sucked into the drains. I know better. The drains were too far from where I had dropped the bracelet, not that mom believed me.

I also hear the diving team is easy for beginners to pick up even without prior gymnast experience, and you can participate in competitions if you’ve learned enough dives. Make sure you go in headfirst and you’ve got a dive, nothing more to it, I think. A straightforward A leads to B, as different as it could get from Dad’s sporadic outbursts when he noticed I was sharing dinner with the family rather than memorizing flashcards, or memorizing flashcards rather than having dinner with the family. I couldn’t eat without squeezing my eyes shut anymore, even when Dad wasn’t around.

The senior divers on the team look like birds swiping fish out of the ocean. They leap from the one-meter board and perform their twists and flips as though warping space-time with their maneuvers, bending air with their muscles.

They enter the water with a splash, briefly disturbing the silence, and I watch, expecting them to resurface in a few seconds but also preparing myself to never see them again, in case someone really does get sucked out of our reality from the deep end.

Mel is also the quintessential example of failing upwards – something we’re all a bit salty about since she slacked off throughout middle school and into high school. I’d see her Facebook posts of half-nudes and beer pong rounds and rides in glossy Porsches with slick-looking guys whom I’ve never seen around school.

The folks who knew Mel through elementary school tell me she used to work hard when we were just learning cursive and grammar, but the effort never got her anywhere. In fact, she was quite bad – bad enough for her classmates to remember many years later. Some people just can’t learn no matter how hard they try, they say.

I think it’s because Chinese doesn’t have any verb conjugations so, when it comes to English, Mel uses the infinitive form more often than not. Things like: “Introduce my” instead of “introducing my,” “soon I go to school,” “yesterday I eat the fish.” She was probably mocked. If I’d been in her elementary school, I would’ve mocked her, if it meant no one would detect my mess-ups with third-person conjugations.

I moved to Mel’s school district in seventh grade because my dad was offered a relocation bundled with a promotion, and he decided he’d never receive another opportunity to become a manager if he didn’t seize it now. Dad isn’t career-driven, but he likes to brag about things he has that his friends don’t have. One of those things is a “leadership” position – one where white people and senior people report to you rather than the other way around.

Mom told Dad it’d be a political cesspool, but he insisted, and I guess the huge jump in compensation was enough to convince her. She didn’t want to live in an apartment where hot water ran out within two minutes of showering.

Mel is always with guys too. Her gaggle of guy friends often sit on the benches to watch her diving practices. I don’t like when they visit. Their stares make me feel like a flounder springing from the board, flailing in the air, plopping into the water like a particularly fiber-fueled piece of crap in the toilet. Mel’s pike, on the other hand, looks like someone has wrapped cast tape around her legs and back, sealing her chest to her upper thighs. You can’t even slip an index card between her upper body and legs.

The other girls like it when Mel brings along her boy toys, but don’t like that she’s the best diver. They try to pull off their hardest, riskiest dives when the guys are around, but their efforts result in more belly flops instead. While we warm-up, Mel tells me the guys are just trying to get into girls’ pants, which is all they think of.

“Why do you bring them to practice?” I ask. As much as I don’t feel like unzipping my jeans for them, I also don’t want strangers’ impression of me to be a drowning duck flopping off a Duraflex board.

“They take videos on their phones so I can review my dives later. I don’t care if they hook up with the other girls.” She looks over as I complete five more rowboats: my flexed feet and loose, bent limbs, my dying abs. “I can help you with your form.”

“It’s fine.” No amount of coaching is going to eliminate the freak-outs that erupt in me just before my hands hit the water. I’m afraid that if I rip too perfect a hole through the water, create a vacuum for my body to enter, suffocate the splash deep below the surface, the whirlpool-black-hole-entity at the bottom will eat me up too. I’d rather mess up the dive than get dragged to who-knows-where.

“Don’t you want to get better though?” Mel asks. Mel is the only one in the gym two hours before practice and one hour after practice, doing cardio, pilates, strength training. She hardly has a chest, and I don’t think she’s ever gotten her period during the sports season. Once she dumped out her bag in the locker room, and instead of the typical protein bars and tampons, small packs of trimetazidine pills and aspirin tumbled out instead.

Sometimes I think she might snap into a heap of bones and hair upon making contact with the water, but instead she tears her way through the water with hardly a ripple.

“I don’t really care,” I confess. Forget my fear of the deep end: I already have my varsity letter to tack onto college applications. I’m not so noble as to seek self-improvement. Trying too hard sets you up for failure—a conclusion I’d made after Dad flung a bamboo cutting board at me because I’d flunked my chemistry final despite weeks of studying. I told him it was because one of my classmates stole my glasses so I got dizzy halfway through the exam, but he didn’t believe high schoolers were capable of sabotage, never mind a classmate who already stood at the top of the academic food chain.

Mel shrugs. “Well, if you change your mind.” She slaps her blue shammy against her thigh and steps forward in line to the diving board. I watch her from behind, the muscles in her calves flexing and loosening. Her swimsuit rides slightly above her hips, wraps around her straight, plank-like waist – not a single dip inward or rounding outward of her flesh, a polyurethane-wrapped ruler that’s all edges and corners. The rest of us jiggle at least a little bit when we move. We are jello people, dumped out of our molds.

When it’s Mel’s turn, we all watch. I stand to the side so I have a better view of her jump. I can’t even get my jump right: not tall enough, not strong enough, too far out of a projectile, too inconsistent.

Mel points her toes like they could be daggers. Her somersaults and twists remind me of a Chinese yo-yo getting flung through the air. This all happens in seconds. She enters the water before I register that she’s added another twist from her usual dive – how and when she mastered the extra 360 degrees, I have no idea.

The water inhales her.

I’m more concerned about not freezing myself. Mom won’t buy me a proper shammy so I have to constantly ring a bundle of old cotton t-shirts dry before wrapping it around my body to soak up the chlorine. Mom insists she needs to save money, but I think she just doesn’t want to admit she doesn’t know where to buy shammies – she thinks Amazon describes a rainforest and hasn’t figured out how to launch a browser.

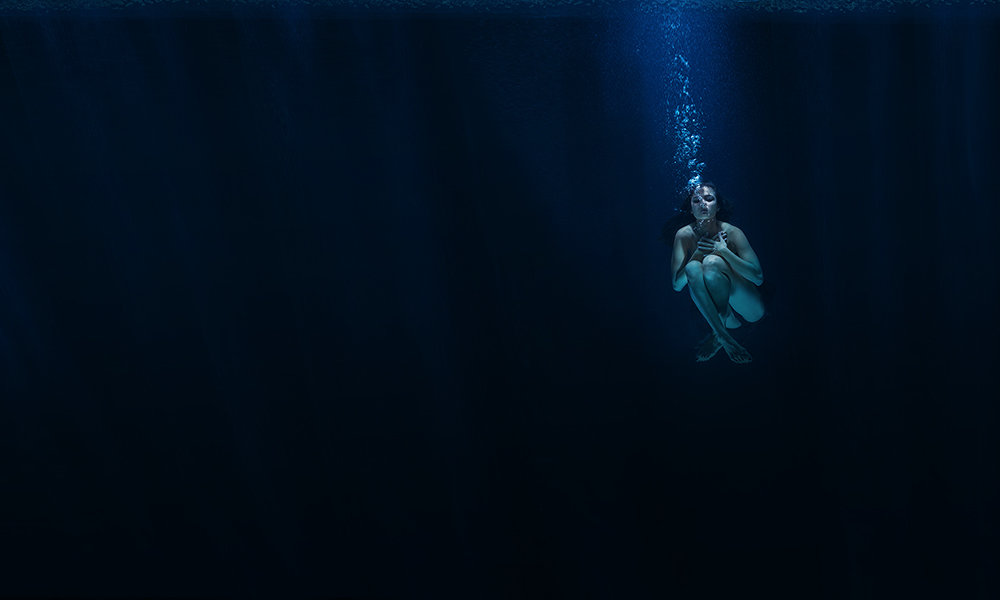

I don’t see any bubbles. No splashes of water. Only faded echoes of kids taking swimming lessons on the shallow side of the pool. None of the other girls move as I walk to the edge of the pool and try to peer past the water surface. I can’t see past a distorted reflection, but that’s the problem with deep pools: they muddle everything, eat up light instead of reflecting it.

“She’s gone,” I say.

The girls step away from the diving board and walk over. They whisper to each other: what does that mean, “she’s gone” – maybe she cracked her head, got concussed – but then she should float back up – at least at first, right? They don’t look at me, even though I’m the one breaking the news, but it’s normally like this. The other girls are part of a carpool rotation and have sushi-and-samosa parties after every meet, and even though I’m invited they know I can’t go, because the bus doesn’t stop in their neighborhoods, and they don’t have room for me in their parents’ SUVs.

But Mom is convinced quitting the team means I lack dedication, even though I’ve acquired the varsity letter, which is what colleges care about. Plus she’s worried I’ll get fat without a sport, and how would she explain that to my aunt and uncle who use every opportunity to size up their daughter against me – test scores, height, skin quality, zodiac birth year, Chinese school ranking (even though the rankings are meaningless since we cheat on those exams). All the shivering and freezing on land must be incinerating the pudge. At least you’ll be the only one with an A4 paper waist, Mom says, more to herself than to me, whenever I come up short in some other category.

Mel’s boy toys stand from the bleachers and walk toward the pool. The other girls start grooming their hair and sucking in their stomachs, even though there’s not much you can hide when you’re as good as naked in a skintight suit. I wait for the boys to look into the pool because I don’t trust my eyes. I tend to miss what other folks see, or see what others insist doesn’t exist – although when I ask mom if I need therapy, if my brain has gone haywire, she chortles and tells me to stop thinking stupid things and wisen up, be rational, no such thing as mental issues.

But the boys never make it to where I am. They stop near the other girls. They laugh and flirt and lightly brush some girl’s arm. The girls laugh too.

“Your boy toys aren’t very faithful,” I mumble, head down.

I see no sign of Mel.

My limbs grow tired and oxygen short. I reach a hand out toward the depths, propel myself deeper, just a bit, trying to scrape the tiled bottom just to prove to myself it’s there even though I can’t see through the dark, but my fingertips flow through without hitting anything solid, water resistance and nothing else.

Time to give up. I begin kicking upward, seeking the surface and oxygen relief, but as soon as I change directions something grabs my ankle.

I look down at the hand clasped around my ankle, the slim, veiny, muscular arm. Mel’s head and upper body peek out from this impenetrably dark void that reminds me of the mugs of pure, unsweetened, bitterness-in-full-force Ban Lan Gen that Mom would force down my throat when I got a cold.

Don’t you want to come? she mouths. It’s nice down here. You never get hungry, never need to leave. There’s no one else.

I shake my head no. I want to breathe. And though the surface seems so far, further by the second, I’m tempted to try.

What would I be resurfacing to? Boys who don’t see me, and girls who choose not to. Mom and Dad’s idea of my future, not mine. And the vanishing ripples left behind by Mel’s absence.

I look down into her eyes, pits like fermented black beans. Her free arm drifts loose at her side and the edges of her hips seem blurred by the water. Her body looks more ghost than girl, the water threatening to dissolve her into chlorine.

I wonder if I can recover from inhaling water, banking on my respiratory system being so evolutionarily adaptable it can filter the oxygen and expunge the water like gills.

If I voluntarily fill my lung sacs with water, can that still be called drowning?

The void Mel is reaching from is so much closer than the surface, so I grab onto her hand. As she pulls me down, I grip tighter.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Balk on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)