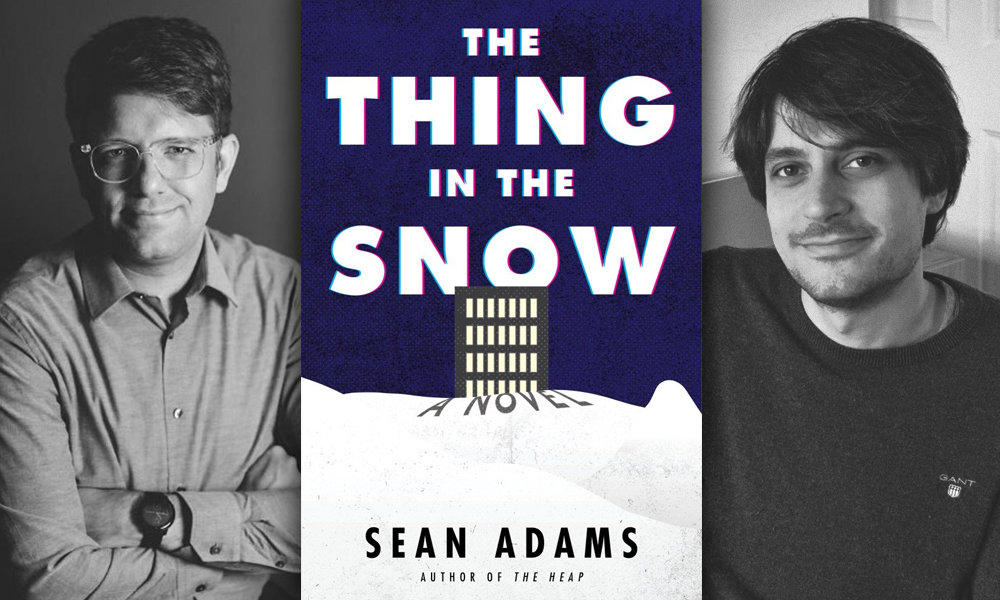

The Thing in the Snow, by Sean Adams

Mattia Ravasi

Every morning I log into my laptop. I answer colleagues’ emails and help my company’s customers. Some days, I feel that my work has had a positive impact on the world. Some days, I’m not so sure.

I go for a short walk at lunch time. In the evenings I sit a few feet from my desk, reading, writing, or watching TV. I go to bed knowing full well what tomorrow has in store for me.

I mention all this to explain why the basic premise of Sean Adams’ The Thing in the Snow did not feel nearly as suffocating, maddening, and panic-inducing as it should have. I suspect that anybody who’s been working from home (or living at work?) for a while now will have a similarly uncanny feeling – and so will everybody who still remembers the long, muddled weeks of the Covid lockdowns.

A small team is camped in a remote research facility known as the Northern Institute: a gargantuan six-story building in the middle of a desolate expanse of snow. Hart, the novel’s narrator, is their leader. He is driven, ambitious – and racked with insecurities. His direct underlings are Gibbs, aloof and distant and harboring ill-concealed career aspirations, and Cline, who is eager and friendly, if just a little useless.

Something is clearly wrong with the Institute. Hart’s team are not allowed to leave it, since a strange sickness swiftly overwhelms anyone who ventures outside. The first two floors are buried under perennial snow – so why did the builders put in so many windows? The greatest mystery of all is Gilroy, a deranged scientist who stayed behind when the rest of the research staff was evacuated, and who is absorbed by his nightmarish research on the pernicious evil that is “the cold”.

Hart’s team, however, is not there to investigate any of this. They are not cold-weather survivalists, or scientists, or scholars of the paranormal. They are, for a lack of better words, corporate peons. They work from nine to five, five days a week, with a coffee break at the start of each day. Each week they are given a task to complete, a list of Karate Kid chores that never seem to germinate into any epiphany: sitting on all the chairs in the building to make sure they are stable; opening all the doors to check for creaks and squeaks.

The Thing in the Snow reads almost as a spoof on Annihilation, Jeff VanderMeer’s novel of disorienting horror, where a team of highly-trained explorers brave an abandoned region whose alien atmosphere might, or might not, be playing with their minds. Hart’s team are not highly trained. They’re not even good office workers. Hart savors his pointless tasks, eager to prove himself before his manager Kay; but he is also painfully aware of his limitations, and of how the corporate ladder – the notion that his managerial position identifies him as a more capable individual than his subordinates – feels flimsy and wobbly in the stark environment of the Institute. His self-consciousness is what makes his frequent pettiness so convincing, and never off-putting.

Hart’s life is not just all work and no play. He goes to great lengths to keep his weekends separate from his weekdays: stopping himself from thinking about next week’s tasks, and refusing to engage with his co-workers between Friday night and Monday morning. This decision seems, at best, futile, considering that his weekends are spent in the same handful of rooms he occupies the rest of the time. Meanwhile, his pastimes (going for walks, reading) appear almost as aimless as his work tasks.

Work, however, comes to dictate even the nature of these hobbies. The books Hart reads all belong to the “Leader” series, a bizarre mashup of thriller and self-help guide, focusing on a Tom Clancy-esque protagonist named Jack French. These books, like all of Hart’s provisions, are shipped to him through the company, and he wants his choice of reading material to make a good impression – “to show Kay that I take seriously the responsibility bestowed upon me, hence the appeal of a series of thrillers about leadership.”

The Leader books are one of the funniest running jokes in the novel. Their plots are just exaggerated and edifying enough that I can see my CEO recommending them in his monthly email. They are also a convincing example of how Hart’s career has collapsed not just the barrier between his living and working environment, with the Institute coming to serve as both. The corporate mentality has started to colonize his mind, too, making him second-guess what type of intellectual nourishment would be best suited for his career progression.

This corporate blindfold is made most noticeable by Hart’s refusal to engage with the mysterious thing in the snow: an unspecified object suddenly appearing on the horizon in the opening chapter, jarring within the otherwise uniform landscape. Hart’s subordinates Gibbs and Cline are understandably eager to learn more about the object, but to Hart the thing is dangerous, and its threat is one of distraction: it could easily become a drain on productivity.

The rest of the book captures the slow unraveling of Hart’s sanity. Paradoxically, what pulls it apart is not the unknowable mystery (and the inexplicable behavior) of the thing outside his window, nor is it the impossible isolation of his living conditions. It is his team’s failure to keep up with their weekly tasks: building a replacement office chair; pulling on all the blinds to see if any are broken. Corporate life – completing allocated tasks, supervising an efficient team – has become Hart’s new reality, while reality, in all of its maddening insolvability, is a distraction that must be put out of mind.

In the novel’s most poignant scene, Hart abandons the once-sacred distinction between office hours and “free” time and works through the weekend to catch up on the tasks his team have accumulated. He enters a peculiarly focused state, becoming entirely absorbed in his menial chores. It is a poignant, disturbing scene. Are we supposed to cheer for Hart? To admire the way he has carved purpose out of purposelessness? Or should we really be concerned at this final collapse of his identity?

What this scene testifies to is the collapse of the barrier between Hart’s personality and his job description. He has confused his value as a person with his ability to complete his paperwork by the given deadline. This paperwork, submitted weekly via helicopter courier, is Hart’s only means of communicating with Kay, who lives far away and, we assume, in much cozier quarters. In an early scene, when he is still in relative control of his senses, Hart reflects on his ardent desire to stick a personal Post-it note to Kay onto the official paperwork. Kay has discouraged this in the past, and yet Hart’s urge is nearly irresistible. The motives behind this urge feel both natural and deeply meaningful:

I often desire to apply a Post-it note because there are times when it feels like the application of a Post-it note is all I can do to reinforce my existence and remind myself that the tasks we are given here are not merely completed (as is noted on the paperwork) but experienced.

This is a very luminous, very human feeling, one that I have certainly experienced myself, and that should be familiar to everybody who has seen weeks of their lives reduced to mere lines on a spreadsheet entitled “annual performance” or “customer feedback.”

I have talked at length about the satirical aspect of The Thing in the Snow. This shouldn’t suggest that the titular mystery is just a prop for the novel’s reflections. It is precisely the narrative’s obsession with Hart’s petty agenda and pointless worries that makes the occasional intrusion of the Institute’s weirdness all the more disconcerting. The team might be bogged down in a silly quarrel on the correct way to complete another task, only to stumble headfirst into a previously unnoticed side of the Institute. The enigmatic Gilroy has a knack for making a shocking appearance. And looming behind every page is, of course, the thing in the snow, its mystery growing more compelling as the novel progresses, its call harder and harder to ignore.

The supernatural aspects of The Thing in the Snow have a way of creeping up on the reader, like well-timed jump scares in a horror movie. Together with Adams’ dry, winning humor, they propel the narrative forward with great momentum. The feeling that something ominous is afoot, that the whole novel could explode at any moment, is what makes it so enticing – and, inevitably, perhaps what dooms it, too. Any resolution, whether open-ended or neatly wrapped-up, is likely to disappoint at the end of a novel where so much could happen at any time.

Ultimately, it is not how well its plot is resolved that makes or breaks The Thing in the Snow. As a compelling mystery and an engaging satire, one that will speak closely to anyone who has felt isolated and trapped in their daily life, The Thing in the Snow is a reminder of the endless ways in which speculative, fantastic, and imaginative fiction can operate: opening doors to the most mind-bending realms, or holding up a mirror to our drab home offices – and always reminding us quite how weird everyday life is.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Mattia’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)