An Interview with Francesco Verso

Andrew Leon Hudson

I won’t wait so long for my second convention. I had an excellent time: caught up with a few old friends and made a few new ones, attended some fascinating panels, talks, presentations, and readings, and of course bought a lot of books, happy to take advantage of the rooms of publishers, authors, and other artists hawking their wares.

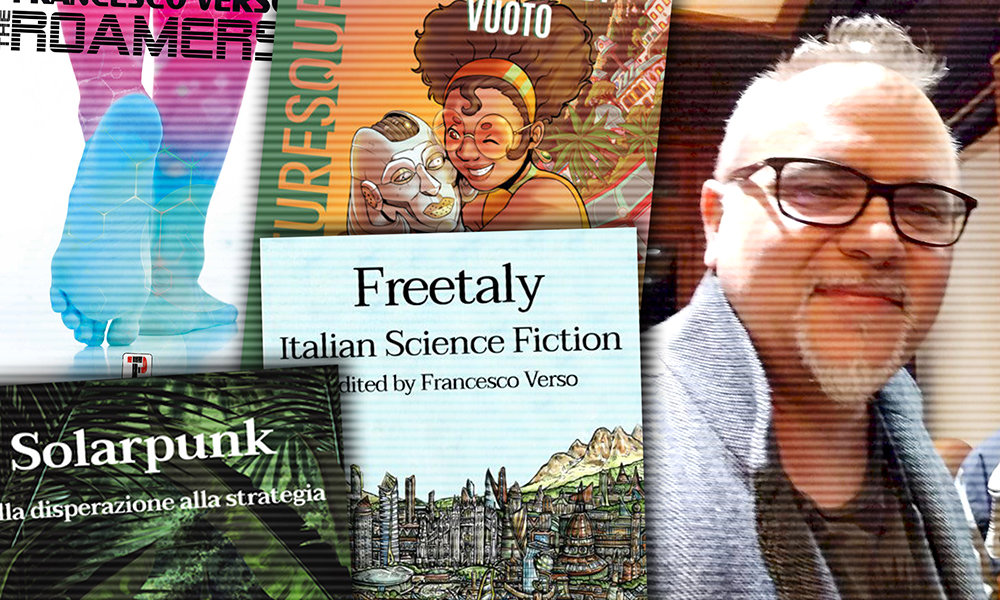

At one stand my eye was caught by a translation anthology of contemporary Italian science fiction, Freetaly, edited by one Francesco Verso, who it turned out was also sitting behind the table. Yet not only an editor, and not just an sf author of short stories and novels too (those roles often going hand in hand), but also co-founder of FutureFiction.org, which aims “to disseminate and promote an interdisciplinary approach to the idea of the future, using science fiction and speculation as bridges between today and tomorrow”.

I thought that sounded pretty interesting, and though our conversation then wasn’t long enough to fully reveal all, it went well in both directions: he waved me off with my arms filled with books, and I walked away with his promise to be interviewed.

Andrew Leon Hudson: Hi again Francesco, thanks for taking the time to talk! Maybe you could begin by telling us a little about yourself?

Francesco Verso: I was born in Bologna, Italy, in 1973, and I studied Environmental Economics at the University of Roma Tre. Before I became a writer full time I worked in the IT industry, including eight years with IBM and two with Lenovo, but in 2008 I quit to dedicate my life to writing and publishing sf. Over the last fifteen years I’ve won two Urania Mondadori Awards, the Odissea Award, the Italia Award, and four Europe Awards for Best Editor, Best Publisher, Best Work of Fiction, and Best Magazine. Since 2014, I’ve worked as editor of Future Fiction, a small press dedicated to publishing the best SF authors from all over the world. We have translations from thirteen languages and thirty-five countries, the only science fiction press in the world to do this.

ALH: What first attracted you to science fiction?

FV: During my university time, I studied for a year in Amsterdam for an Erasmus project. There along the canals I found a little secondhand bookstore run by an American guy who, down in the basement, was keeping hundreds of sf books. Frank Herbert’s Dune, Ian McDonald’s Desolation Road, William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness… So I started from there, with the crazy ambition of imitating the writers that I now consider my teachers and sources of inspiration.

I write only science fiction, and I set my stories in the near future and mostly on Earth. I can’t really write about other worlds, as I believe there are enough alien realities and otherness here on our planet to light up any sense of wonder. We already walk into many uncanny valleys. Lately I am interested in exploring the solarpunk and human augmentation subgenres – sustainable energies and posthuman issues driven by technologies like CRISPR-Cas9, 3D printing, biomimicry, and native innovation – as tools to explore and analyze the biopolitical scenarios we’re heading towards in the coming years.

ALH: Tell us about your first success as an author.

FV: Oh, it was a long time ago… Back in 2008, I sent the manuscript of my second novel, e-Doll (a techno-thriller where sex-shifter androids are used as prostitutes to limit the awful phenomenon of sex-crimes), to the most prestigious Italian sf award, the Urania Mondadori Award. I was just an absolute beginner, so I am really thankful to the editors at that time, Giuseppe Lippi and Sergio Altieri, who gave me an opportunity to be published that has literally transformed my whole life.

ALH: And how about your most recent one – I have a copy of The Roamers waiting on my TBR shelf (so not too many spoilers please!).

FV: The main theme of The Roamers follows the life of a group of social rebels at the twilight of Western civilisation who undergo an anthropological transformation caused by the dissemination of nano-robots capable of reassembling molecules to create new matter. This technology changes the way they feed themselves and gives rise to a creative and autonomous culture which, while based on 3D printing and mesh networking, is in some aspects reminiscent of an ancient nomadic society.

The book was published in Italian in 2018 and it’s the first example of solarpunk novel in Europe, at least that I am aware of (other novels may have a slightly solarpunk vibe, but are not clearly or openly solarpunk). It’s now been translated in English by Jennifer Delare and published by Flame Tree Press; Chinese and Tamil editions are due to be published in 2024-25.

ALH: Tell us about your experience of having your work transformed this way.

FV: Translation is very special to me. It’s the real bridge to other worlds, other stories and futures. Without translations we would be doomed to live in just one reality, the one we’re born in, missing all the beauty that lies outside our own culture. As soon as I was published I started to think about the translation problem, and it was very difficult and complicated to invest my own money in the translation of my novels. Finally I found Sally McCorry who – over the course of more than ten years – has helped me translating three novels and around twelve short stories, becoming my “English voice”.

In the specific case of The Roamers I worked with Jennifer Delare. I couldn’t pay the kind of fee that a big publisher could offer, so I had to be part of the process in order to make it happen, and after some twelve months we managed to finish. She was translating around two to three chapters at a time, and then sending them back to me for checking and approval. Jennifer did an amazing job, and not just on her own work; she found some minor contractions and missing information in the original text, and thus her contribution has also been relevant to revision of the Italian second edition as well as the English release. She was able to capture the original voice of the story and so I’m very grateful for what she’s done for me.

Without making an initial investment myself in my translation, no editor in Science Fiction would have ever read any of my work, as there simply isn’t the interest within the publishing industry to explore non-English language fiction. Now that I’m also being published in other languages, the translation experience is changing for me. In the case of English, I am able to control more or less the meaning and even some nuances of the final translation; but with Chinese, for example, I just have to share with the translator as much as possible in terms of tone and atmosphere, and then trust in their work.

Basically, the translator is the primary writer of your novel’s derivative language – not an easy task at all. And my science fiction is full of neologisms, plays on words, and cognitive estrangement, so it’s really a fine work of art to do translation well.

ALH: This brings us around to Future Fiction. It seems to me that a big part of what you’re doing here is broadening the potential audience of individual writers by breaking down the barriers of geography and language.

FV: Yes. Being an Italian writer is to live at the margin of a new dominant English culture, so over the last ten years I’ve come to realize that there’s a huge cultural loss to global science fiction in translations only coming from English. I’ve been invited to many sf cons – in France, Spain, Croatia, China, India, Montenegro, Finland, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands – and I always ask editors the same question: “What language do you translate from?” The answer is always the same.

There was a time, from the 1960s through the 1980s, when important works of speculative fiction were translated from one country to another throughout the world, especially in Europe, Russia, and Latin America. Today, however, the hegemony of English in the publishing world has created a situation in which every author wants to be translated into English. This means that everyone knows everything about American and British SF while completely ignoring what is being written next door, in France and Germany, China and India, Brazil and Argentina, Poland and Finland.

In reality, of course, high-quality science fiction is being written everywhere in every language; it is just that for most publishers commercial concerns come first, so readers do not necessarily end up with access to the best writing, just to the ‘best’ books available in English. This also imposes a huge and unfair burden on any people that do not speak English, many of whom do not have access to language instruction or cannot afford to study it. There is a lot of work to do in this respect, not just on markets but mostly on the perception of reality and how storytelling should and could be.

The cultural loss of such a short-sighted approach is huge. A study by the University of Rochester found that only 3% of what is published in the US comes from a translation. Similarly, on any SF shelf in any bookstore from Tokyo to Amsterdam to Roma to Rio De Janeiro, there are hundreds and hundreds of books translated from English, and few from each nation’s own writers or writers writing in languages other than English. That is what Antonio Gramsci would call a ‘cultural hegemony’.

ALH: How did Future Fiction come to be?

FV: It all started because, as an sf reader, I was missing a huge part of the representativeness of the complete real world, some kind of “literary biodiversity” which in other genres (as paradoxical as it might seem) is not so unusual. For this genre to really become international, it should include the voices and experiences of people naturally speaking Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese, French, Spanish, Hindi, Japanese, Bengali, Russian, and German, just to mention the most commonly-spoken languages. I was looking for the missing voices of global science fiction.

So the project is more like a cultural small press than a commercial publisher. Thanks to a team of translators, we’ve published more than 200 short stories and 60 paperback, plus twelve comics and fifty audiobooks, either in Italian or in dual language formats (Chinese-Italian, English-Italian, and English-Chinese). Some might indeed define this as “diversity”, a term that is increasingly popular in and out of the genre in the Anglophone world, but then I think, “Diverse from whom? Who is in charge of setting the standards of “diversity”? Again, we are back to the original bias towards English-speaking culture.

We talk about the precariousness of monocultures in biology, but what would the world become if there was just one voice to talk about the Future? And just one religion or economy or lifestyle to represent it? So, just as the Seed Vault in the Svalbard Islands preserves the biodiversity of plant life from a possible environmental catastrophe, I’ve set myself on a quest to preserve science fiction’s literary diversity from a possible cultural catastrophe.

ALH: What plans and objectives does Future Fiction have looking forward?

FV: Well, during the first phase of this project, the mission was to demonstrate that “science fiction happens everywhere” and, believe me, it was not easy at all to achieve it. Often people at book fairs or sfcons say, “Oh, is there sf in Italy? Or in Turkey, or Greece, or India?” So now this small project has developed into a real storytelling engine aimed at the “decolonization of the future”.

The majority of big sf publishers in any country are more interested in what’s “around” the book than what’s “inside” it, and they don’t have scouts for other languages. We use a very powerful tool that I call the Sense of Wander to give dignity and visibility to Science Fiction stories that, because are not written in English, would remain neglected and totally ignored by the global conversation. Great books, wonderful authors, incredible scenarios, all lost “like tears in rain…” ☺ Our plan is to establish a network of small presses across the world that will talk to each other, share the best authors and stories, and translate directly between non-English languages.

ALH: And how about yourself – do you have anything interesting on the horizon?

FV: Two of my novels, Nexhuman and Bloodbusters, were published in China last year and soon they will also be released in Malaysia. The Roamers will come out soon in India too. I believe that the future is coming at full throttle from the East, and thus I will continue to work on that side of the world. I am about to finish a solarpunk anthology of short stories called Ecolution in the same setting as The Roamers which will be released in Italian and English next year, and I’m also working on the adaptation of Ecolution and Bloodbusters to comics published by Futuresque, the comics imprint of Future Fiction. 2023 and 2024 will be busy!

Thanks again to Francesco for chatting with us. If you’d like to actually hear him speaking about his passions, check out his 2020 presentation on Solarpunk as a genre and a social movement at the InterWorldView Conference in Huangzhou, China. You can get hold of his own publications here, and if you want to explore the Future Fiction website you’ll be glad to know it’s available in both English and Italian!

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)