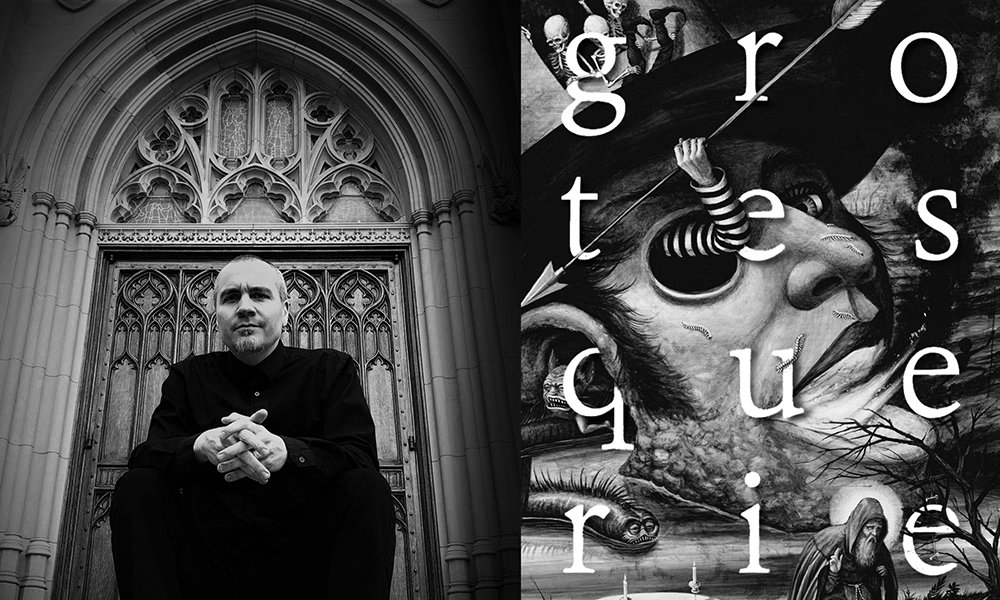

Grotesquerie, by Richard Gavin

Bill Ryan

The world of horror literature is full of such writers (and by the way, just for the record, this is not necessarily a sign of quality): Mark Samuels, Quentin S. Crisp, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Reggie Oliver… This even happens to writers who were once in the mass market. For example, look at The Voice of the Clown by Barbara Brown Canary. That was once a mass market paperback. When you get your hands on an affordable copy, let me know.

I don’t mean to overstate things here. Other than Canary, several books by each of the writers mentioned above are readily available, in print, at different levels of affordability. But not all of them, especially their early books, like Samuels’s Black Altars, or Crisp’s The Nightmare Exhibition and Shrike. And theycan even come out of this: the great and immortal Robert Aickman’s full bibliography (save the slim volumes he wrote about England’s waterways) are back in print, as are most of the books by Thomas Ligotti. Thanks to Penguin Classics and other publishers, the vast majority of this master’s fiction is easy to find (strangely, it’s Ligotti’s most recent work that is hardest to come by), making this once-obscure writer’s name somewhat well-known, though I doubt many more people read him now than did before. But his influence is out there, and growing, in ways it never had before, so that while for decades up-and-coming horror writers wore their Lovecraft influence on their sleeves, now the shadow of Ligotti is just as likely to be seen (some may consider this six of one, half a dozen of another given that Lovecraft heavily influenced Ligotti, but on this I am forced to disagree).

Someone who fits into many of the slots I’ve mentioned is the Canadian horror writer Richard Gavin. He is the author of several out-of-print, and now expensive, books (The Darkly Splendid Realm, Charnel Wine, etc.) and several that are in print but not widely known outside of passionate horror circles, such as At Fear’s Altar, Sylvan Dread: Tales of Pastoral Darkness, and Grotesquerie. It is this latter title that, at long last, concerns us today.

And speaking of Thomas Ligotti, as I often am, his influence on Richard Gavin is at times, shall we say, vivid. In Gavin’s story “After the Final”, the unnamed narrator (that’s your first clue) relates to his professor the story of one night when he and his “companions” set out to prove they are “true macabrists”. To me, this alludes to Ligotti’s belief, at least at one time, that among horror writers he was the only one writing real horror. Given Ligotti’s fantastically bleak antinatalist view of life and existence, that case could be made, but this reading is debatable. More explicit is the fact that the professor being addressed is named Professor Nobody. In Songs of a Dead Dreamer, Ligotti’s first story collection, Ligotti included a non-fiction, philosophical essay called “Professor Nobody’s Little Lectures on Supernatural Horror”. The lectures given in the essay are given by Professor Nobody, but I think it’s pretty well understood that’s just Ligotti. Elsewhere in “After the Final”, Gavin drops phrases like “this degenerate little town” and “my work is not yet done”, both of which are titles of Ligotti works. “After the Final” is almost like a little game for fellow Ligotti fans, and therefore unserious. Then again, near the end, Gavin writes “But as exquisite as this horror was, I am still left wanting”, which suggests the story could on some level be a refutation of Ligotti’s unlivable philosophy. You don’t have to agree with the man to admire, even love, his work. And we all have our hopeless hours.

But enough about Ligotti. Grotesquerie is my first experience reading Richard Gavin, and it was my presumption, based on certain titles, that his work was firmly ensconced in the folk horror subgenre. And indeed there’s a fair amount of that, or at least nods towards that category of horror (one which I find particularly interesting), but that’s not all Gavin is up to, at least in this book.

Though Gavin was already on my radar, I was led to this particular collection by, of all things, a pair of tweets by somebody I don’t even know, naming Gavin’s “Scold’s Bridle: A Cruelty”, published in Grotesquerie, as one of their favorite horror stories. Having read it now, I concur that it’s a terrific story, set in a modern suburb but with hints toward an ancient folk history that the reader is not privy to. I don’t want to describe the story in detail, because it’s rather short and saying anything about the plot would be to say too much. But it’s truly skin-crawling, a story in which the horror is revealed with unnerving casualness.

There are two other stories in Grotesquerie with titles similar to “Scold’s Bridle: A Cruelty”. Those are “Headsman’s Trust: A Murder Ballad” and “Ten of Swords: Ruin”. Together, these three stories comprise the best stories in Grotesquerie; the latter two are also much more explicitly of the folk horror subgenre.

“Headsman’s Trust” describes the process of rising through the ranks to become the new executioner. This is a gross oversimplification (and a glib one) on my part, but again, while “Headsman’s Trust” is a bit longer than “Scold’s Bridle”, I’m loathe to describe the story in too much detail. At his best, Gavin has a way of simply letting his story, and its horror, unfold at its own pace. This makes the events of the story seem, in a very unpleasant way, like everyday occurrences. But to give you a sense of the kind of mood Gavin can evoke, here’s the first paragraph of “Headman’s Trust”:

Just how the Headsman trapped divinity within His axe blade is a riddle I am not destined to solve. But I have borne witness to the Cut-Lord’s miracles. They evidence the power of both the blade and the hand that wields it. This is sufficient to keep me in servitude to Him.

This paragraph does a lot of work, including informing the reader that we are not in the present day (though I suppose where we are – the past or a post-Apocalyptic future – is an open question).

“Ten of Swords: Ruin” is the last story in Grotesquerie, and by far the longest. Normally, I object to this kind of sequencing, but “Ten of Swords” reads at a pace that makes it seem much more brief than some of the shorter, yet more labored, stories that precede it. It’s about two young sisters – Celeste and her older sister Desdemona – who are often left alone at the family estate by their very strange parents. The story revolves around a hidden Tarot card and a set of matryoshka dolls; also the shocking consequences of when Celeste’s inherent curiosity and mysticism override her sister’s philosophy of leaving well enough alone, and of not doing anything to bring unwanted attention from their parents, especially their mother.

This isn’t to say that Desdemona views their parents unlovingly, or as a threat to their well-being, but she is uncertain about and somewhat afraid of their secrets and what might come from learning more about them. “Ten of Swords” is a psychologically and supernaturally complex story, but there’s one straightforwardly visceral scene of horror that I could see vividly in my mind’s eye. It’s a very effective punch, just when the story needed it.

But as I’ve hinted at, Grotesquerie isn’t a complete success. There’s a formula that many of the stories fall into: our main characters have some normal, domestic sort of problem, one which, as they are diverted from a work trip or other errand, is mirrored by the horrific circumstances they ultimately find themselves in. “The Patter of Tiny Feet” is probably the worst offender in this regard, with its basic idea being set up dutifully, rather than artistically. “Fragile Masks” is another, although I quite liked this story, about a couple encountering the woman’s ex-husband at a bed-and-breakfast. Much more transpires from there, but for the life of me I can’t figure out where the “mask” metaphor came from, or what it’s supposed to mean in the context of this story and these characters. It’s as if Gavin thought he needed a dash of something stereotypically literary to smarten things up. If so, he was wrong; “Fragile Masks” would be better without all that.

So Grotesquerie is a mixed bag. A solid piece of work like “The Rasping Absence” sits in the same table of contents as “Neithernor,” which is initially intriguing (it deals with mysterious and inexplicably disturbing art, a favorite trope of mine) but in the end feels bizarrely rushed, as if Gavin found no time to develop it the way he wanted to. But there are worse reading experiences than reading a mixed bag. There’s enough that’s good about Grotesquerie, and enough in it that clearly shows off Gavin’s talents, that I consider it all a net positive. Bring on Sylvan Dread, I say!

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Bill’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)