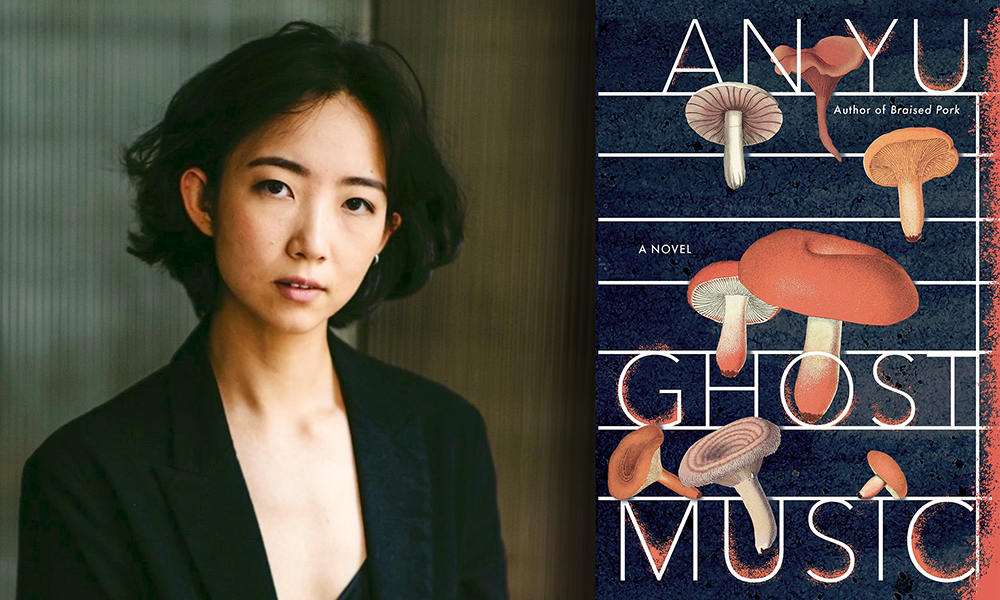

Fungi & Phantoms: Ghost Music, by An Yu

Mattia Ravasi

An Yu’s Ghost Music evokes eerie echoes of Erich Zann. The novel’s protagonist, Song Yan, spent her childhood and youth practicing the piano with the express purpose of becoming a virtuoso – yet in the novel’s present she contents herself with the occasional job as piano teacher after a nervous breakdown put her career ambitions to rest. She lives with her husband Bowen in their Beijing apartment. Her mother-in-law, a proud and distant woman, has recently moved in with them.

The ghost of Song Yan’s forsaken career is the largest and most tenacious among the many ghosts that haunt this sinister, fascinating novel. When one of her young pupils encourages her to play a melody on the piano, Song Yan falls back on a simple, innocuous composition, an old favorite that is unlikely to stretch her skills. Song Yan’s commitment to music is blatant on every page, but she is reticent to explore the outer edges of her talent, as if this were a territory she has sworn to avoid.

A significant portion of the early novel is dedicated to documenting Song Yan’s everyday life: her efforts to get along with her difficult mother-in-law; her painful attempts to connect with her workaholic husband. There is a feeling of airlessness to Song Yan’s life. A sense that things are in too tense a balance to remain stable for long, but that they have also been stuck in place too long to change. This paradox does not make the novel uncomfortable, let alone boring. The way in which Song Yan faces her predicament, trying her best to be kind to her family while carving out a space for her needs, makes it very easy to sympathize with her situation.

There is also a certain bottom-line strangeness to Song Yan’s life that propels the story forward very powerfully. In the brief chapter that opens the book (and I confess to a certain coyness in avoiding this fact until now), Song Yan has an encounter with a talking mushroom: a small orange fungus who appears to her in an otherwise sealed room, expressing a wish to be remembered. The encounter does not seem real, but it’s not quite a dream, either.

Soon enough, Song Yan starts receiving unexpected deliveries of vacuumed-packed mushrooms. Her mother-in-law accepts these mystery packages enthusiastically, embracing the culinary possibilities they offer. She and Song Yan stew the mushrooms, pickle them, add them to stir fries. There is something uncomfortable about this kitchen alliance. Just as Song Yan’s life seems perfectly poised between normality and crisis, this new hobby she embraces is at once wholesome and unsound. Should one really trust mystery mushrooms so easily?

Mushrooms provide the perfect foil for the other great force in the novel, music. Both are mysterious and otherworldly. Both are nourishing and provide sustenance but can easily take a life away, either through a deadly poisonous fungus or by turning into an all-consuming obsession. When asked by a pupil whether she likes the piano – a typically childish question, straightforward and yet impossible to answer – Song Yan admits that she has no way to know, because the piano has loomed so large over her entire life. It’s too big a part of her for her to know how she really feels about it.

Mushrooms and pianos become fused together in the fulcrum of the novel’s plot, the first of a series of twists that finally knock Song Yan’s life off-balance. As she investigates the sender of the packaged mushrooms, Song Yan finds herself welcomed into the home of Bai Yu, a virtuoso pianist who disappeared ten years prior without leaving a trace.

The parallels between Bai Yu and Song Yan are obvious: she gave up on her talent right when her career was meant to begin; he retreated from the limelight as he was poised to achieve his greatest triumph. Bai Yu is almost a ghostly embodiment of Song Yan’s past, or better, of the future that she renounced. It is significant, in this sense, that her father, a pianist of some renown who cut all ties with her after she abandoned her career, was a great admirer of Bai Yu and much shaken by his disappearance.

This is not the only ghostly aspect of Bai Yu’s character. Asked about the reasons why he decided to disappear from the world, he confesses to a strange phenomenon he encountered as he developed his talents:

“The more time I spent with the piano […] the more it seemed like my hands didn’t belong to me. The sounds didn’t come from me. I became frightened to the point that every time I was sitting at the piano, I couldn’t help but feel that there wasn’t a ‘me’ at all.”

Unable to play any longer, Bai Yu is looking for someone to help him “find the sound of being alive,” a sound which he seems to believe is trapped inside his piano, waiting to be released. His research is at once deranged and brilliant: an old man’s folly, or a supreme act of artistic daring. As she is recruited into helping out with this endeavor, Song Yan is plunged right back into the lively, ambitious side of her creative self.

Ghost Music, however, is not a story of redemption and unlikely comebacks. It is, instead, very much a ghost story: a tale about people confronted with the traumas of a past that won’t stay asleep, and that imposes itself on the present in ways that are disturbing and even brutal.

An Yu masterfully unpacks this process of shock in all of its harshness and pain. The same delicate bravado is on show in those sections of Ghost Music that deal with Song Yan’s marital difficulties. In the early part of the novel, her husband Bowen is not so much mean to her as blind and deaf to her needs, her very presence. It is easy to read him as a terrible person. Yet, as we come to learn about his own ghosts, his character slowly acquires more dimension. If we don’t quite forgive him, we can certainly understand him. It even becomes possible to see his own dedication to his employer as a very similar impulse, if somewhat less refined, to Song Yan’s consuming passion for the piano.

After she has endured a number of tribulations – and more encounters with the talking mushroom – Song Yan reflects on her relationship with Bai Yu, and remarks on his importance in her life in a powerful passage that speaks to one of the deepest functions of art: it might not take our problems away, but it reframes our focus and expands our gaze, giving us a deeper appreciation of the strangeness and vividness of life.

There is much in Ghost Music that I haven’t mentioned in this review. Presences from Bowen’s past come back to haunt him. A mysterious orange dust plagues the novel, appearing at various points in time and space. Ghost Music is not quite a work of magical realism, but it’s also not simply a realist novel with “surreal” elements. Instead, it brilliantly short-circuits the expectations of the ghost story (some of its ghosts, for instance, are not dead, at least not yet) while preserving its central tenets: a preoccupation with “visitations” from an uncomfortable past; a sense of uncertainty before these events that pushes its characters to question their grip on reality. That it manages to convey all this in a way that is at once impactful yet subtle, all while offering a wistful but charming portrait of life in modern-day Beijing, is nothing short of magical.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Mattia’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)