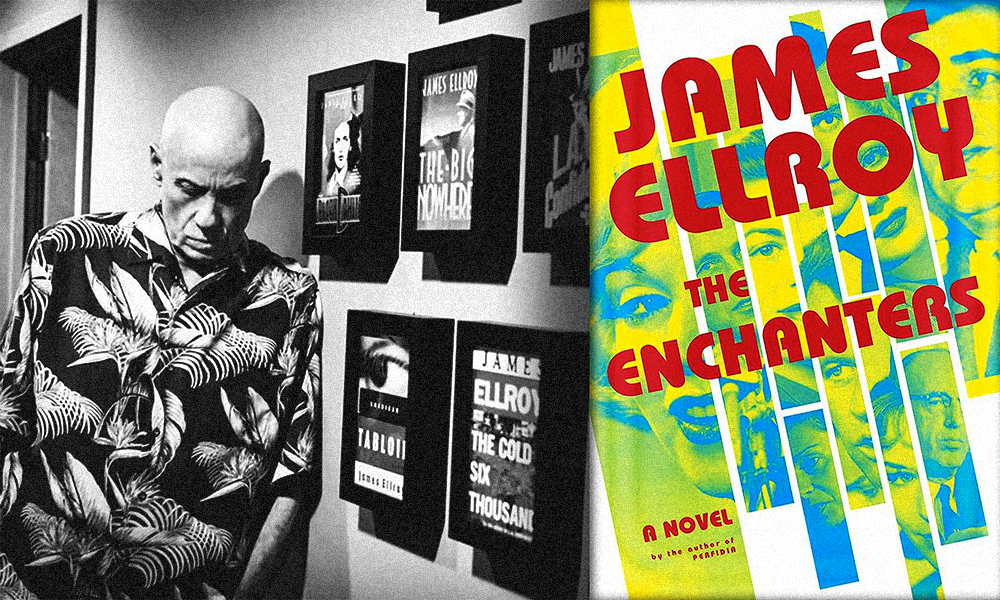

The Enchanters, by James Ellroy

Bill Ryan

Well, to be as brief about this as I can, the staccato, almost telegraph style that he’d perfected in L.A. Confidential (that original L.A. Quartet, as it’s come to be known, is the primary basis for my Ellroy fandom) seemed to take over his brain, and I found the extreme version of that style difficult to connect with in his Tabloid follow-up, The Cold Six Thousand (I skipped Blood’s a Rover, as it was a sequel to a book I hadn’t read). My only excuse for not yet reading Perfidia or This Storm, the first two parts in his new L.A. Quartet (parts three and four have yet to appear) is that these days I find the vast length of those books to be a touch daunting. And I faltered again when he took an unexpected break to start a new series, featuring former L.A. cop, former private eye, and former Hollywood tabloid reporter Freddy Otash (a real fringe historical figure), because the first book, Widespread Panic, was written in a maddening alliterative Hollywood tabloid style that, frankly, repelled me.

But finally, here we are, with his new novel, The Enchanters. Also featuring Otash, but working, basically, as a cop, and no longer a tabloid reporter (hence no, or very little, alliteration) things appeared to be, for me, clear sailing. And indeed they were. Here is how chapter one ends. You should know that Otash and the legendary Hat Squad (again, real historical figures) have picked up a couple of known perverts, and are trying to shake, or beat, them into revealing what they know about the recent kidnapping of B-movie actress Gwen Perloff. Otash and one of the Hat Squad guys have hold of one of the perverts, named Richard Danforth, and are dangling him off a cliff overlooking an L.A. freeway. So:

Red said, “You’re wearing us thin, Richie. We can’t keep this up all night. Tell us where the girl is, so we can walk away from here.”

Danforth giggled and spit on Red’s shoes. He said “I’m having fun.”

I slid on my brass knucks and kidney-punched him. He stifled a screech and dug his feet in. I looked over the cliff. Cars zigged by – fast, with no letup.

Max sighed. Red sighed. Max said, “Sink him, Freddy.”

They dropped their hands. I shoved Danforth off the cliff. He treaded air for one split second. “It’s a put-up job” came out garbled. I heard him hit a car roof. I heard brakes squeal. I heard wheels thump over him. Crisscrossed headlights lit him up. A pimpmobile Caddy dragged him against a guardrail and sheared off his feet.

And we’re off. On to chapter two.

I don’t know what any of you think of the above passage, but for me it was bracing, invigorating, to the degree that I thought “Ellroy’s back.” Never mind the fact that as far as I knew, he was back ages ago and I just hadn’t read that, or those, books. But here I was, all in.

The plot really kicks off a little bit later, with the death of Marilyn Monroe. It is her death, and life, and vices, and strange psychology (at least as Ellroy describes it) that propels everything, even if by the end she’s less a player in the dark circumstances of the hidden aspects of her life and death than she is a tool of violent perverts, drug dealers, and unsavory psychologists. That of course does not mean that any devotee of Monroe and/or her legend will think, while reading The Enchanters, that Ellroy has done right by her. From the moment Ellroy published The Black Dahlia in 1987, he had apparently become committed to writing historical crime novels – prior to that he often wrote crime novels with a contemporary setting, but after Dahlia he hasn’t written one. So his novels are populated by historical figures, and he’s very rarely nice to them. John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy appear in The Enchanters (the latter quite prominently) and Ellroy seems to genuinely hate them. I don’t know that I’d say he comes off as hating Marilyn Monroe, but he certainly doesn’t buy into her mystique, and he doesn’t consider her the victim of Hollywood, misogyny, and Hollywood misogyny that many do (me, I’m staying out of it). At one point, he has Freddy Otash – certainly a man who’s earned his jaundiced view of Los Angeles and the humanity, such as it is, that can be found therein – as he investigates Monroe’s death, wonder why she was such a big deal with legions of fans, when he himself was not particularly drawn to her sexually, and she wasn’t even a good actress. This will rub a lot of readers the wrong way, which I can understand. My own feelings about Monroe are far more kind, but I wasn’t bothered. This is James Ellroy. You buy your ticket and you take your chances.

Speaking of hate, Ellroy – though a writer who has taken much from classic film noir, and an unabashed fan of certain actors, especially Sterling Hayden – truly does seem to hate Hollywood. Which is entirely understandable. This also means that among the historical figures that appear in The Enchanters (which also includes Darryl Gates, the eventually notorious chief of the LAPD, depicted here as a police lieutenant with no small amount of influence) are some notable Hollywood folk. Peter Lawford, for example, and Darryl Zanuck, who is tied to kidnappee Gwen Perloff, and whom Ellroy portrays rather unfavorably. On the other hand, Roddy McDowall, functioning here as someone who knows all the Hollywood gossip, comes off relatively well. Heck, at one point Freddy Otash even says that he likes McDowall. That sort of warm feeling is almost unheard of in Ellroy.

The ongoing production of the infamous flop Cleopatra, which McDowall was in, shows up here as a kind of backdrop, both as the motivation behind certain events and as a general reminder of foolish Hollywood excess. This means that Elizabeth Taylor also shows up briefly, to sleep with one of Lawford’s bodyguards and spill some beans about 20th Century Fox.

So there’s lots of stuff going on in The Enchanters, and most of it has to do with the sleazy, hidden corners of Hollywood. And of psychotherapy. In Ellroy’s version, Monroe was fascinated by, and committed to, strange and perverse lives of crime, usually those of a rather obscene nature. This led her to consult with psychiatrists who specialized in sex and sex criminals. This ties into what will eventually become the main thrust of the plot, which has to do with a “sex creep” breaking into the homes of divorced women and leaving all sorts of messages (sometimes better described as “messages”) behind, including morgue photos of Carole Landis. Landis was an actress who killed herself (according to Ellroy, I admit to not knowing the facts) because her lover, the right bastard Rex Harrison, wouldn’t leave his wife to be with her. She also functions as the proto-Monroe.

That’s about as far as I’m willing, or able, to go by way of plot summary. I don’t really think any more is required, but that’s not why I’m stopping here. James Ellroy’s novels are famous for having exceedingly complicated plots. And often, when reading his fiction, there will come a point where I realize I’m missing something somewhere. He’ll mention a character in a way that suggests I should know full well who that is, but I don’t. Or why the characters were led to a particular place, or why so-and-so did such-and-such. When this happens, I think “Well, James Ellroy is a pro. I’m sure he knows what he’s doing,” and therefore blame myself entirely. This is probably fair, so I have no problem taking the heat, though it can be a little exhausting. This was one factor in putting down The Cold Six Thousand as early as I did – an Ellroy plot in a nearly 700-page novel written in extremely short, clipped sentences seemed to me to be a recipe for getting completely lost, and I try to keep the moments in life when I feel badly about myself to a minimum.

But it honestly doesn’t matter. By the end of The Enchanters everything was fairly clear – certainly the gist was. Everything works out nicely in that regard, and anyway the thrill of Ellroy’s fiction is when the reader finds themselves vicariously shoveling through the mud and shit alongside, say, a drunk, violent, pill-popping Freddy Otash, with his colleagues, most of whom he can barely stand, and his nemeses, who he wants to see lying dead at his feet. There’s a scene of violence late in the book that outdoes the one I quoted before, and which slams directly up against the title of Part 10 of the novel in a way that was so grimy that I almost wanted to cheer.

Again, I imagine this novel will not sit well with some of its readers, but I can’t imagine any Ellroy fans clutching their pearls over it. This is a James Ellroy novel. You should know by now to prepare yourselves.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Bill’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)