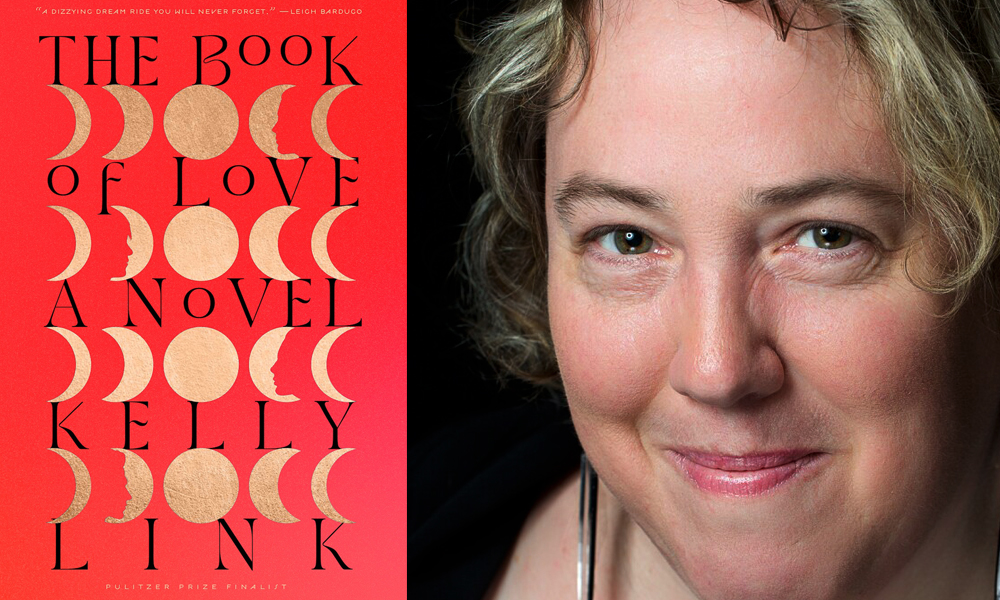

The Book of Love, by Kelly Link

Mattia Ravasi

Kelly Link eviscerates the magic of this liminal age in The Book of Love, a novel obsessed with doors and transformation, with dreams and ambitions burning hot in the hearts of its characters. Set in the quaint seaside town of Lovesend, Massachusetts, the novel focuses on a group of teenagers who are back home for Christmas… from the dead.

The townsfolk might be convinced that Mo, Laura, and Daniel spent the last few months at a prestigious music school in Ireland, but they know better. They were actually dead, trapped inside the interdimensional realm of a trickster god called Bogomil. Somehow they managed to escape, bringing with them a fourth person, a remarkable individual called “Bowie” (after a poster in Lovesend’s high school music room) who does not seem to know their own identity.

Collectively they are confused, disturbed, and scared, though still able to crack the odd joke. As they strive to puzzle out the events of the past year, particularly the mystery of their own death, the four of them get tangled up in a game between Bogomil and the local music teacher, Mr. Anabin, a laconic man with a passion for motivational t-shirts and who is also a capricious god.

They are free to go back to their families and resume their lives, for a time. But in the end, while two of them will be allowed to stay, two will have to return to Bogomil’s nightmarish realm.

This tight, cruel premise allows Link to showcase the full range of her fabulist powers and stylistic flair. A giant in the field of fantasy fiction, Link has won most major awards you can think of, including a MacArthur Fellowship “Genius Grant” and three Nebulas. She is perhaps the most obvious successor of Angela Carter as a writer able to take the material of myths and fairy tales and extract from it its deeper psychological and emotional meaning, while also preserving the significance of its outer shapes, its Gods and monsters, refashioning these stories into a guise at once recognizable and extremely modern.

Link, however, is renowned as a short story writer. The publication of her first novel thirty or so years into her career cannot but be an intriguing prospect. Does The Book of Love pack all the genius of her shorter work, taking it to new heights? Or does her work feel dispersed and diluted in long form?

The Book of Love is incredibly funny, especially considering its central theme of teenage death, whether the humor comes from Mo’s sass or from Laura’s explosive fights with her volatile sister Susannah. Its prose is lush and luxurious, baroque perhaps, but never purple. Through vivid descriptions, meaningful anecdotes, and a knack for a winning simile, Link manages to bring the whole of Lovesend to life, in a way somewhat reminiscent of another fictional New England town, the Derry depicted in Stephen King’s It. The reader experiences the beauty and boredom of this quiet tourist spot, its charm and also its dullness, through the eyes of people who know it like the back of their hands, who love it quietly and implicitly but also can’t wait to be rid of it. Lovesend is a place where crushes, exes, and rivals are inescapable; where the few attractions available (like coffee shop What Hast Thou Ground?, whose owner, of course a loveable grump, inevitably doesn’t like customers who linger too long but is fiercely protective of his baristas) are shrouded with the mythical aura of all the memories that accrued around them, from first kisses to ill-advised hookups, nighttime escapades and days full of laughter.

The early part of the novel is as rife with mystery and drama as you would expect from the balance of reward and loss in its stunning premise. The newly returned teenagers get to grips with the life they had left behind, with all the things – some of them tragic – that have happened since they “went to Ireland”. Their manipulative gods have tasked them with doing magic, which they set out to do in ways that speak volumes about their character: Laura with zealous drive, Daniel with resigned stubbornness, Mo skeptically… while Bowie turns into a seagull, and then into a whisper of moths.

All too soon, however, this magical premise starts snowballing into a mythical avalanche, as new god-like creatures are introduced, the protagonists swiftly turn into fearsome magicians, and Lovesend becomes the setting for a showdown of cosmic proportions.

While it is hard to pinpoint an exact moment when The Book of Love grows unwieldy, by its final third the novel has become a succession of scenes where all-powerful beings talk wittily about magic, cracking one joke after another. Between one dialogue and the next, all of the characters find meaningful and rewarding love in the arms of handsome strangers or long-cherished crushes. The sense of imminent danger animating the early novel is lost. Any intimations that their cruel predicament – two shall live, two return to death – might push the four protagonists to betray each other are swiftly forgotten in the name of friendship and support, with strains between them no more than an occasional, and swiftly-resolved, misunderstanding. One of the harshest conflicts comes from Susannah getting mad at her sister because Laura used magic to force her to do the laundry.

The Book of Love is extremely switched-on and politically correct. It is set in a town filled with statues of African Americans of great achievement, who, at one point, come to life and tear to bits the statue of a slave owner. All the characters are respectful of their friends’ personal spaces and privacy; lovers act toward one another with nothing but tenderness and understanding. All of this is incredibly admirable, but it makes the novel feel somewhat lifeless, plastic, a magical showdown set in a version of our world that is a little too sanitized to feel convincing. In time, even the novel’s villains turn out to be tenderhearted, while its supervillain reads very much like a larger-than-life baddy, Cruella De Vil with godlike powers. The more one reads The Book of Love, the harder it is to believe that even its original threat-cum-promise – that two of its protagonists will meet a terrible end – is unlikely to be kept.

It goes without saying, but there is of course nothing wrong with characters having healthy relationships, or with satanic death gods who turn out to be altruistic, loveable scruffs. The Book of Love is certainly very aware of what it is doing, and speaks at length – through the character of Mo’s grandmother, a successful romance writer – about the nature of love stories and our need for happy endings. The result is a very funny young adult novel which contrives to pitch its characters in situations where its humor can be best exploited. Back-cover comparisons to The Master and Margarita, while spectacularly out of place, are certainly not the book’s own fault.

Ultimately, The Book of Love is characteristically Linkian in its strangeness, but also the literary equivalent of a peanut butter mocha fudge hot chocolate, a refreshment typical of Lovesend’s quirky coffee shop: any balancing trace of bitterness is overwhelmed by the saccharine sweetness of everything else. It’s by no means a bad concoction, but do you have the stomach for six hundred pages of it?

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Mattia’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)