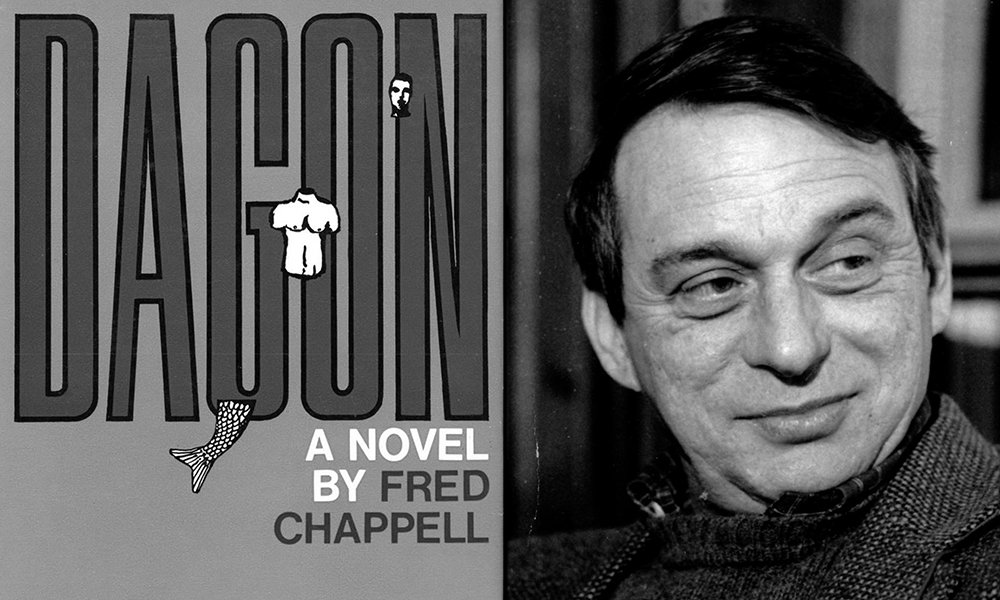

Dagon, by Fred Chappell

Bill Ryan

I’m on record as being something of a skeptic when it comes to Lovecraft. There’s no need to re-litigate that here, but I’ll go ahead and admit that “Dagon” is one of his better stories (his very short stories tend, in my view, to be better than his longer ones, and “Dagon” is pretty short). I particularly like the way he describes the key moment, when the narrator sees the aquatic god Dagon himself (or Himself). Spoiler, I guess:

Then suddenly I saw it. With only a slight churning to mark its rise to the surface, the thing slid into view about the dark waters. Vast, Polyphemus-like, and loathsome, it darted like a stupendous monster of nightmares to the monolith, about which it flung its gigantic scaly arms, the while it bowed its hideous head and gave vent to certain measured sounds. I think I went mad then.

Anyone familiar with Lovecraft, but who somehow has never read “Dagon,” can probably guess that all of this ends with the narrator leaping from his apartment window to his death. Standard Lovecraft. Still, a good story. But in my experience, it is the writers who fell under the sway of Lovecraft’s vast influence, and wrote their own takes on the man’s mythos, who rise above what that depressed, mentally ill Rhode Islander laid out for them. The stories written by the Thomas Ligottis of American horror fiction, say. Or, and this is what brings us here today, the third novel by a prolific North Carolinian poet named Fred Chappell.

The title of that novel, by the way, is Dagon, so no one can accuse Chappell (who died this past January, at age 87) of trying to hide his influences. Published in 1968, Dagon is, from what I can tell, a bit of an outlier for Chappell. Then again, what do I know: as of this moment, other than this slim horror novel, I haven’t read a word of Chappell’s fiction or poetry. But while his first novel appears to be a fantasy story, the novels he wrote later in life sound to me like somewhat gentle stories about life in small-town North Carolina. Chappell wrote many books of short fiction, so there could very well be loads of horror fiction strewn throughout those volumes. I’m very curious to find out, because if there’s one thing Dagon is not, it’s gentle.

And what a unique riff on Lovecraft’s story it is. It’s the story of Peter Leland, a minister and scholar. His grandfather has recently died, and Peter and his wife, Sheila, have inherited the old family home. This includes a not insignificant amount of land, so large that the Lelands soon discover that a family, the Morgans, live, and have lived, on a section of the Leland family property, though Peter never knew about them. They are an odd, backwoods, off-putting family – Ed Morgan, the patriarch, is caught leering at Sheila; when Peter visits their home he encounters a wife who never speaks, and a daughter, Mina, whose appearance (“That body so stubby and that face so flatly ugly – something undeniably fishlike about it…”) makes him uneasy, and somewhat obsessed: “…her flat dark face hung like a warning lantern in his mind. He couldn’t unthink her image.”

Additionally, in exploring his ancestral home, Peter finds reams of paperwork and letters to and from his grandfather. There are not-so-subtle references to Cthulhu in this material, which is interesting to me because there are no such references in Lovecraft’s original short story; he hadn’t written, or at least hadn’t published, anything about Cthulhu yet. But, as many other writers influenced by Lovecraft have done, Chappell wanted to create, or complete, a fabric that Lovecraft in his short life wasn’t quite able to do. Chappell even includes, after his novel’s dedication (“Dedicated to Those Who Cast Their Shadows Out of Time Upon Our Days”), as a kind of sub-dedication Lovecraft’s famous words “Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn” which, in one of his stories, Lovecraft translates, resulting in possibly the finest sentence he ever wrote: “In his house at R’lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.”

More importantly (thematically anyway), though harder to parse in relation to the rest of the book, and even harder to summarize here, is the monograph that Peter is writing, and which he hopes to complete amid the peace of his new home. It has to do with Dagon, the Philistine god of the Hebrew Bible, and whose temple Samson destroyed. Chappell, via Peter Leland, goes on to describe how some people throughout the world continued to worship the debauched god Dagon, a worship that even gained a foothold in America. He quotes from William Bradford, a governor of Plymouth Colony, who wrote about how the inhabitants of Mount Wollaston:

…fell to great licentiousness and led a dissolute life, pouring out themselves into all profaneness. And [colonist Thomas] Morton became Lord of Misrule, and maintained…a School of Atheism. And after they got some goods into their hands…they spent it as vainly in quaffing and drinking, both wine and strong waters in great excess…

A description of Pagan lasciviousness follows before Bradford describes the arrival of John Endecott, who:

…caused that maypole to be cut down and rebuked them for their profaneness… So they or others changed the name of their place again and called it Mount Dagon.

Leland uses this material to write sermons about what he saw as a modern, metaphorical worship in America of Dagon, given what he views as the rampant and public sexuality now present (remember, this book was published in 1968).

Before I make Dagon sound like an essay, I should stop talking about this part of it right about now. But it’s fascinating, and leads the story into depths of thought and philosophy that might be described as oceanic (forgive me). Lovecraft, of course, never gets into any of this, though he obviously didn’t pull the word “Dagon” out of a hat. Yet his main pre-occupation, as far as that title goes, appears to have been what I’ve since learned is an etymological misinterpretation of the origins of the name. Without getting into it too much, for many years “Dagon” was believed to be related to another strain of fish-based mythology, and this was still accepted in Lovecraft’s day. If his interest in “Dagon” the word went beyond this, and into the Biblical source, I don’t know for sure, but from what I can find it seems not.

Whatever the case, Chappell sure found a lot to work with, and his story evolves (or devolves, depending on how you want to look at it) into one about a rapidly and disturbingly fractured marriage (about which I dare not say more), and then into a kind of eerie road trip story involving Peter, Mina, and a cruel yokel named Coke Rymer. For reasons I won’t get into here, by this point Leland has become a zombified (not literally) version of himself, quiescent, controlled by a kind of moonshine fed to him by Mina, a moonshine notable for its oiliness, stupefying effects, and general nastiness.

It’s difficult to write about this section of Dagon, as there isn’t too much to say about it unless I’m willing to tell you about the ending. But I really don’t want to ruin it for you, as the ending – and by “ending” I mean literally the last two or three pages – is the best part. It is, really, a fantastic, smart, deeply unsettling ending, one that kind of throws Lovecraft into a cocked hat. Unless I’m misreading something in its final pages (always a possibility), there’s even a kind of terrifying hopefulness to it. If the last chapter landed for me the way Chappell intended, it’s not a hopefulness that warms the heart, but it causes the cosmic madness and terror of Lovecraft to sort of blossom into something that at least allows for questions and wonder. The answers to those questions might lead us, like Lovecraft’s narrator, straight out the window, but we won’t know unless we ask.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Bill’s thoughts on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)