Headspace

Mark Martin

My neurologist, Dr Constance, felt very differently on this subject. He was a booster for the science, keen I should join Candace among a population of isomorphs barely in double digits. I’d often thought, and mentioned to my wife, Charlotte, several times, that dying would be less frightening if guaranteed to occur against a backdrop of mountains and tumbling waves, watched over by a lidless sky. Despite his dizzying professional stature, Constance’s office couldn’t be further from that. Between inoffensive impressionist prints, the space was cramped and oppressive. The framed photographs on his desk kept their backs to his patients. The harsh light made my palms sweat.

“I can understand your discomfort at the thought of an isomorphic future,” he said. “The earliest of the subjects has been observed for only a little over a decade, though they are all doing well physically. In every way, their health is normal. We scrub the genotype of identifiable risk factors, but it’s possible isomorphs will have a shorter than average lifespan because of the reduced telomeres of the host body. Longer than the alternative, of course. We can’t be absolutely certain yet of the lifetime stability of our wetware, but the results so far are all pointing in the right direction.”

Just hearing him on the subject triggered an insistent throbbing behind my temples. “You said she underwent the procedure as a teenager,” I said, pinching the bridge of my nose. “Wouldn’t it make more sense for me to talk to someone closer to my age?”

“She doesn’t live far from you. But, location aside, she might be the person best suited to allaying your concerns. She’s a very smart young woman who pursues the kind of quiet pastimes you’ll appreciate.”

“I’m sure she’s a regular, everyday reincarnated heiress to the ultrarich. What did she die of?” The question was blunt as a cudgel, but my head hurt.

The doctor was unfazed. “An unusually aggressive form of cancer that was caught very late in the day. Just like your own case.”

I nodded, noncommittal. Had I been diagnosed when I was Candace’s age, I would have been dead long ago. These days, medical advances appear so frequently a terminal diagnosis is likely to strike any patient as provisional, and immuno-therapy had extended my life expectancy from months to years, but the new treatments still come with pain and risk.

There was a bone sickness that left me jack-knifed on occasion. I frequently suffered the wracking nausea of pitiless migraines – and thinking too deeply about the prospect of isomorphism was always likely to set one off. One salvo of therapeutic chemicals had turned every hair on my body milk-white, even my eyelashes. When my natural colour finally came back a couple of months ago, Charlotte smilingly ran her fingers through my restored dark beard. I had to laugh; she had claimed to prefer the snow fox look.

Dr Constance’s voice intruded on my thoughts. “Candace travelled a long hard road before the procedure, and it was rough going on the other side as an isomorph. It’ll be the same for you.” He cleared his throat. Recently, he had taken to brushing away my symptoms with a nonchalance that made me wonder if he had grown tired of my endless prevarication and would as happily see me dead as isomorphic.

As he explained many times, cancer would get me in the end unless I made the leap. If its final assault made a beachhead in my brain, I would lose the option to become an isomorph altogether. “And,” as he had observed in our very first consultation, “how many people in your position have an opportunity such as this? It is quite a gift.”

A humble classics professor, drawn to monuments of unageing intellect, immortality – literal or figurative – had never been on the cards for me. Tech moguls, hedge fund barons, kleptocrats made up Dr Constance’s clientele. But a single day of Jan’s earnings could more than cover the cost of my resurrection. Why he offered to pay was anyone’s guess. Maybe capacity alone was reason enough, a momentary Why not? Or perhaps the oddity of having such an insignificant person preserved as an isomorph appealed to his impish sense of humour.

Years ago, long before he became the asteroid-mining trillionaire of global fame, Jan had been a student of mine. A favourite, I blush to admit. A hard-drinking, boyish, jovial undergraduate, he treated study as a game and picked up Ancient Greek as other people pick up colds. He loved Thucydides especially, the early master of realpolitik, but it was the work of a different Ancient that resonated in our phone conversation: domesticated, dog-loving, moralising Plutarch – light years distant in character from Jan.

Debating Plutarch’s famous thought experiment, the Ship of Theseus, was always an easy way to chalk off a class. For centuries, the Athenians preserved the ship of their founding hero, but over time its timbers warped and rotted. One by one replacement parts were found and installed, until eventually not a single plank or dowl remained of the original. In what sense then, if any, did this remain the ship of Theseus?

Was it a new ship? If so, at what point in its history of piecemeal renovation did it cease to be that famous vessel? Or was it still the same one? If so, what if all the discarded timbers of the original construction were somehow recovered and put back together? Which would be the ship of Theseus then, when the incremental replica and reconstituted wreckage floated side by side?

Jan’s answer was simple. If there were two versions, and ownership of both was attributed to Theseus, on coming back to life the hero could claim them both – and no Athenian should stand in his way. Possession was ten tenths of existence. The debate wasn’t about a state of being but a brand: they were both the ship of Theseus. Problem solved.

So much for ontological niceties. Jan cut the Gordian knot, laughing at the idiocy of eye-rolling undergrads baffled by age-old word games. Was he the most advanced of my students or the most obtuse?

These events instantly came to mind when I first heard of Jan’s unsurpassable flaunting of scientific taboo. And they of course came back to me again when I got off the call in which he offered to transform my life in the most profound of ways through the magic trick of keeping it exactly the same.

I took it as a sign she was preparing for the end. Or the beginning.

On the way, we spoke on the phone to our teenage children, Julian and Diana. Together with Charlotte, they encouraged me to visit Candace Terry. Their positivity was unsettling. They might have been chivvying me to join a backpacking excursion. They claimed to be neutral on the isomorphic question, respectfully avoiding anything that might apply pressure, but for the first time it sounded like their minds were made up: the kids wanted a father, Charlotte a husband.

What I couldn’t bring myself to explain was the conviction they would get instead a doppelganger, a usurper of the dinner table and marital bed.

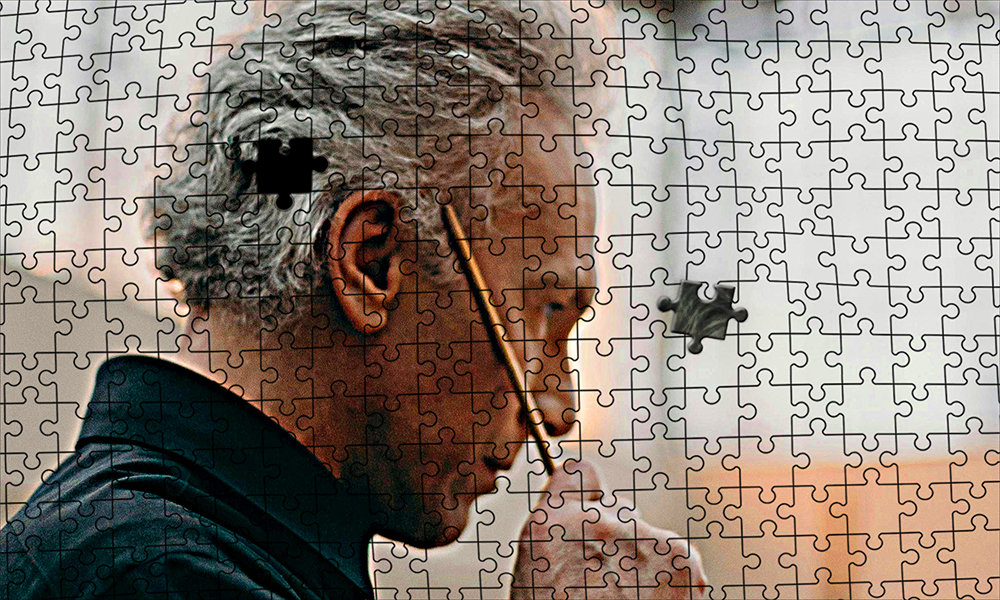

If I were to go through with the procedure, my memories and drives, my talents and weaknesses, would be reconstituted in the blank grey matter of an adult clone, making it that thing of flesh and blood that is an isomorph. My new vessel would walk the world free of cancer, released from fear and pain. The tight corners of my family’s eyes would loosen. I would be reborn. At least, that was the idea.

To complete the transition to isomorph, the brain scan requires a healthy organ, which I still had to offer. Yet, in the process of copying, that original matter would be thoroughly destroyed. Not a whiff of it, not a coil of smoke, would hang in the air of the operating theatre. Where would I be then? Would I be there at all?

Ultimately, I relented and agreed to meet Candace. Dr Constance made arrangements, and later the next day her mother, Jacqueline Terry, appeared full-length in our living room window, her translucent image floating before our view of the woods at the edge of the property. A regal figure, dark ringlets filigreed with silver, bare feet beneath wide linen pants, she won me over in an instant. I trusted her.

“You still live together, don’t you?” I said. “You and Candace? Is she available to come on the call?”

“She thought it best that the first time you meet it should be in person. You should come alone, she likes her privacy. And we ask that you respect her feelings by signing this NDA.”

The cat pawed at the windowpane as the document text descended the glass like an autumn leaf. I gestured, and my digital signature was appended.

Jacqueline smiled. “Spend the weekend with us at the farmhouse. You’ll be very welcome.”

A snatch of verse swooped pleasantly through my thoughts:

Little soul, charming wanderer,

Guest-companion of my flesh,

Dear departing pallid loner,

Heed the time and stay no longer.

Your jokes will fall on ears grown deaf.

The Emperor Hadrian wrote those words on his deathbed around nineteen hundred years ago (any faults in the translation are mine), addressing his soul as if it were a separate being. The independence of his ‘little soul’ struck me as peculiar. Did it possess anything of the character of its host, or was it just an animating spark? A force of nature doesn’t normally suggest something ‘charming’ and inclined to jokes. But who knows?

Is it possible there was nothing of Hadrian in Hadrian’s soul? Had he been alive today and been given the option to become an isomorph, the tables would be turned on his animula. The little soul, that vital spark, would have been thrown aside, while the speaking voice and tastes and knowledge of the emperor lived on.

On that long northward drive, I felt myself pulled between the spiritual and the material. I thought with gratitude of my family while waves of deep summer green washed about the car, precious reflections surely nourishing some vital part of the human composition. But still there was a suspicion I was merely romanticising pleasant and momentary sensations.

Are the finer feelings of existence happy accidents, the equivalent of being woken by a lover’s touch to realise it’s only the morning breeze mussing your hair? If the lover were there, would the moment of anticipation be any sweeter?

I had expected some domestic lickspittle to greet me. Instead there was Candace’s grey-bearded father, Beau. He jogged gamely down the glass-and-steel stairs, shawl-collared cardigan trailing like a cape. Soft-spoken and solicitous, he showed me where to park and charge my car. Inside, we moved along a wood-panelled corridor decorated with reassuring family portraits to a cavernous central living space. We might have been the building’s sole occupants.

In deference to my English origins, Beau produced a steaming pot of tea and laid out snacks that looked homemade. We settled in what he called the ‘conversation pit’, a square of seating recessed into the floor beneath the steepling windows of the living room. Before us a meadow declined toward a paddock. All of this was invisible to the electric eyes long-established in the heavens.

“I understand one of the Jan Drivers has offered to pay for the procedure?” Beau said, pouring the tea. He might have been asking about my holiday plans.

“Yes, the Good Jan. The original was a student of mine. I guess my course made an impression.”

He cocked an eyebrow. “The original?”

I feared a faux pas. “Does that sound odd?”

“A little, but don’t worry. Candace would be the last person to take offence. I have to say, yours is a peculiar situation.” Smiling and avuncular, he handed me a cup. “The Jans are quite a pair, aren’t they?”

Indeed, they were. If Jan Driver’s features were close to ubiquitous before his accident, they became inescapable once worn by the two celebrity isomorphs who replaced him.

Details about the car crash are vague. There are theories he was brain-damaged when making the decision to grant the world a double-helping of his genius, and that for ethical reasons the scanning shouldn’t have gone ahead. That’s before one even considers the can of worms popped open in the production of two identical beings doomed to compete for the same identity. The rumours ran wild.

But what Jan did was very much in character. Having disrupted whole economies, why not take aim at identity itself? Besides, as with Alexander the Great, the idea of leaving a legacy for rivals to fight over would have pleased him. He might have died with the same command on his lips as Alexander: “To the strongest!”

For a while, in the public eye the two Jans fraternised nonstop. They walked abreast on red carpets and once or twice made business presentations as a double act. But the tipping point was Sonia Alverez, the pop star and branded avatar who’d been dating Jan at the time of his accident. Both isomorphs expected to resume the relationship, but Sonia hadn’t signed up for this unique form of polyamory and made her pick of the two, insisting on a subcutaneous microchip to confirm the chosen one’s identity when they met.

The rejected isomorph retaliated. The individual thereafter known as Bad Jan went public with all the infidelities and deceptions practised on Sonia before the car crash by his originator. In turn, his counterpart expressed contrition in a very un-Janlike way. Good Jan began to dress in loungewear, grew out then tamed his hair, and started to behave very much like a normal adult, albeit one with limitless wealth and diverse global (and solar systemic) business interests. He and Sonia became engaged, while his leather-clad opposite happily kissed them both off and pursued the life of a rockstar. For each Jan to be a success, distinct identities were required.

“Good Jan saves favourite teacher from death,” I said. “It’s a pretty good headline. Should bump the share price for a day or two.”

“Do his motives matter to you?”

“I think they might. Is that silly?”

“I’m not in your shoes.”

“You might be one day – thinking about becoming an isomorph, I mean.” He had the money after all, unless it had all been spent to save his daughter. “Things happen.”

“I might consider it.”

Jacqueline entered, her very natural smile enduring all the way through the long walk from the hallway to our place below the tall windows. We shook hands, and she invited me to ask about Candace.

“What was it like from your point of view? The procedure and what followed?”

“At first, when she came home, Candace was on cloud nine,” said Jacqueline. “It was a joy to witness. She was so happy to be alive, to feel healthy again. She spent every day on long country walks or reading. She looked up every friend and acquaintance she’d ever known.”

“She cooked us complicated meals,” said Beau, “inviting her friends to join us on a culinary world tour, a different national cuisine every weekend. Always playing with the dog, always smiling. It’s called early-stage euphoria.”

“We didn’t know it was common,” said Jacqueline. “We were expecting her to be confused about the procedure. We were told denial was typical, but instead she was ecstatic. At least, at first she was. Then she crashed.”

“Plummeted,” added Beau. “It was heartrending. We expected some sort of correction, but nothing so catastrophic. We started to wonder if we’d condemned her to a life of depression.”

“It was much worse than expected,” Jacqueline said. I had no need to question them, really. They clearly found in me an opportunity to voice things most often left unspoken.

“As well as depression, there was anger.” Beau raised the teapot interrogatively, and I shook my head. “She was furious with us.”

“Candace was fifteen at the time,” said Jacqueline. “A minor. Naturally, we’d discussed everything with her before the procedure. We sought consent. Beau and I certainly thought she had agreed that, in the event she lost the ability to make the request, it could go ahead with our approval. And that’s what happened, that’s what we did. But somehow she got to thinking that she – our daughter – had died in that operating theatre, and that the dying Candace might have stood a chance of survival, however slender, if we’d not requested the procedure.”

“There’s more than that. She said we had never grieved our daughter’s death.” The deep lines below Beau’s handsome blue eyes underscored his words. “She said we had approved the murder of a dying girl in order to avoid mourning her loss. Not only was she an unwilling beneficiary of a crime, but she had to believe we would do it again if the circumstances were repeated. That we’d kill another daughter, we’d kill her a second time, as it were.”

“It was very hurtful. We couldn’t convince her there had been no hope of recovery.” A consoling hand on her husband’s knee, Jacqueline was speaking to him as much as me. “We had no choice.”

“The obtuseness of therapists and psychiatrists is amazing.” Though clearly troubled by these memories, Beau remained amused at human folly. “How could she feel any other way? She’s always been smart. But for all their expensive educations, the professionals were completely taken aback. Quite useless, I felt. Feel.”

Jacqueline frowned patiently at the memory, one hand still on the tiller of her husband’s knee. He put his fingers over hers and they paused.

“But the anger, too, was a phase, I hope?” I said after a moment.

“A rite of passage,” said Beau. “It subsided, and she came out stronger.”

Jacqueline nodded. “Candace is in a much better place now.”

“She is someone new,” said Beau. “Our daughter still, but different.”

“You’ve heard enough from us, you should meet her!” Jaqueline rose, smiling brightly, and took my elbow as we stepped up from the seating area, guiding me towards the window and the deck outside.

“Where is she?”

“At the belvedere, farther up the mountain,” said Jacqueline. “That’s where she spends most of her time. She’s made it very beautiful. Go meet her. Take some treats for the dog.”

I could have tramped that mountain path forever. For the first time in long months the tension deep in my muscles began to thaw. I was going to talk with someone who understood my situation first-hand. Perhaps she could answer the question I rose to every morning from bedsheets twisted with the effort of struggling for an answer. If Candace couldn’t help me figure out what to do, what to tell my family when my mind was finally made up, no one could.

The path levelled out and a white pagoda rose in a clearing. A small wire-haired terrier, a Jack Russell variant, danced around me, announcing my arrival with a bark like bottles smashing. When Candace emerged, the dog orbited the two of us, pausing occasionally to look her way for validation.

Isomorphs have smooth complexions, free of scars and most blemishes, a freshness that leaves them looking younger than their developmental age. But Candace could have passed for a woman in her thirties despite being, in ontogenetic terms, about ten years younger than that. It was a matter of bearing.

“You’ve met Hodge,” she said. “I’m afraid he doesn’t have a volume control.”

“I expect he’s a loyal friend.”

“Yes.” She looked pleased, though she countered the suggestion: “Actually I think loyalty in dogs is exaggerated. But we are great friends, Hodge and me.”

“Will departed pets become isomorphs one day?” The question was glib, but something about Candace told me she wouldn’t object.

“It’s sure to happen soon, if it hasn’t already,” she said. “So, you wanted to meet an isomorph. That’s understandable. Lots of people seem to, but you have a better motive than most. I never asked for celebrity, and it takes total seclusion to buy freedom from the media.” She waved toward her surroundings. “I’m lucky I was one of the first. It’s a harder secret to keep today.”

I could only agree. “Your parents said you found it hard to come to terms with being… becoming what you are.”

“I tortured them, it was ugly. I was the adolescent from hell. From the grave, anyway.” She scratched her dog behind the ear. “Hodge was all that kept me sane.”

“I’m more of a cat person. Does that spell trouble?”

“You’re pretty much fucked.” She was deadpan, and I discovered I liked her very much.

She gave me the tour, showed me her vegetable garden and flowerbed. As we wandered, she quizzed me lightly about my profession, my life history, how I and my family were handling my disease and its one final and questionable cure. I had come to listen to Candace, but – much as her parents had with me – I found a freedom to speak with her that I hadn’t enjoyed in a long time.

She listened attentively. A nod here, a moue there, her reactions dignified and subdued – her mother’s daughter. She smiled when I mentioned the absurdity of my changeable hair, expressed sympathy when I described my migraines and the fears that provoked them.

“I read a lot of philosophy, saw therapists,” she said. “Meditation, mindfulness, self-help – what struck me is how they’re all, whether they recognize it or not, guiding people to live the way animals do all the time. Not thinking about the future, not being tortured by what might be or could have been. Animals don’t even have to try, and they have all of that.”

“Philosophy is the disease for which it is also the cure. I can’t remember who said that.”

“Was it a dog?”

At length she ushered me inside, where I accepted a glass of water. The single room of the pagoda contained a desk, low table, sink, and twin bed; an outhouse was partially hidden among the trees. There were bookshelves, a small library comprising, as far as I could tell, history, science, and poetry almost exclusively. Also P. G. Wodehouse. No philosophy now. There were sketches laid out on the little table, but she didn’t direct my attention to them.

She asked about my connection to Jan Driver, and I started to tell her about the ship of Theseus only to feel silly when it became clear she knew the story already.

“There’s a Buddhist version,” she said. “It’s very old, copied down in Chinese in the fourth century from a lost Sanskrit document. A man travelling between cities spent the night in an abandoned house. He was woken when a demon rushed inside carrying a corpse. Another demon followed, and they started arguing over who was the rightful owner of the dead body.

“ ‘Which of us came in with this corpse?’ the first demon demanded of the traveller.

“There was no sense lying, and the traveller told the truth. The second demon was so enraged at his reply he tore off the man’s arm, and the first replaced it with a limb from the corpse. Seeing this, the rival tore off the man’s other arm, which was again substituted with one from the dead body. The demons continued severing and replacing body parts until there was nothing of the original man left. At that point, they fell upon the newly torn flesh, eating it ravenously before leaving the traveller in his new body, baffled and desolate.

“In the morning, the traveller visited the head of the local monastery to seek advice. ‘You have been blessed,’ said the teacher. ‘It takes my pupils years to comprehend that the self is an illusion, but you have achieved wisdom in a single night.’ ”

“Is that what you think?” I asked. “That there isn’t a self?”

“I feel exactly as Candace always did, but Candace is dead. I’m sure the two Jans both experience the intensity of being Jan. And you think you’re you, and any isomorphic copy of you would think he’s you, too, and transitioning from one state to another will be death and at the same time no more significant than waking up in the morning after a night’s sleep. If you aren’t your memories or your body or the combination of the two, what conclusion is there other than that you’re nothing at all?”

“It’s a bit sad, isn’t it? It’s bad enough dying. To submit to the idea there wasn’t a you in the first place is like dying twice over.”

Candace shrugged. “The decision has been made already, there’s nothing for you to decide.”

The illusory nature of free will has always struck me as a tedious assertion – hard to counter, perhaps incontrovertible, and thoroughly dispiriting. “Buddhism isn’t really my philosophy of choice, I’m afraid. I’m an incorrigible occidental.”

She continued to smile gently. “Try poetry instead. Of the two dreams, night and day, what lover, what dreamer, would choose the one obscured by sleep? That’s Wallace Stevens.”

Sat on the floor with Candace, I scratched Hodge’s flank. He watched me over his shoulder all the while, wary and grateful. “Do you resent what your parents put you through?” I asked.

Her smile grew warm and forgiving. “No, they were always going to be that way inclined. Mum and Dad invented the neural scanning procedure, after all.”

“You were right, all of you, to encourage me to visit Candace, though it might not feel that way when you hear how things went. The main thing is, she helped me come to a decision. This is my decision alone, the most personal anyone could make, and I know by the love you have for me you’ll respect my choice – I feel that more than I could ever put into words.”

I looked down at Charlotte’s hand in mine. “I’m sorry to tell you that the procedure is not for me. I’m not going to be replaced by an isomorph.”

The drive back from the Terrys had given me time to work on my resolve. Without intention, Candace had convinced me the procedure would be quite meaningless. It might be me who went into the operating theatre – if there was such a being – but someone else would come out. What would emerge would be a perfect facsimile, someone else’s vessel, if these vessels of ours are truly steered by anyone.

As for my family, my decision meant they would suffer a loss, but life ought to move on. Since my death would come eventually, why not make peace with it now? And part of me welcomed the prospect of being mourned, a bittersweet motive I would have been embarrassed to admit.

When I stopped talking, the faces of my family spoke of pity and confusion. And something else.

“I’m reconciled,” I reassured them, “I’m fine. Be happy knowing that, please. Everything’s going to be okay.”

Charlotte put her hand to my cheek. “You’re right,” she murmured, “it is.”

They were watching me, measuring my reactions. It suddenly struck me they understood more than I did.

A cluster of impressions flooded me, everything that had troubled me about the isomorphic treatment. For a moment, I felt the awful foreshadowing of a migraine – and then, just as abruptly, it faded. Memories assailed me: Dr Constance’s easy dismissal of my symptoms, and something he had said about Candace and myself; society’s unquenchable thirst for anything isomorphic and Charlotte’s sudden desire for privacy, her infectious dislike of the media; Candace’s taste in poetry, and the full implications of her Buddhism; and—

“My hair,” I said, rather stupidly, at last comprehending the truth of what had happened.

Charlotte smiled. “Yes, John,” she said, squeezing my hand. Who precisely made my wife’s eyes brim with love in that moment, I couldn’t say. I knew only that it was love, and that would have to be enough.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Headspace on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)